The idea of “a nice hot bath” is evocative for many people. It’s an experience to look forward to, an opportunity to reset and recharge, and a deeply indulgent moment of self-care in this world of five-minute showers and dry shampoo. It takes time to draw a full bath, and time to soak; it takes space and solitude, and control. Time, space, water: all highly sought-after commodities throughout human history. Presumably that’s why baths have been associated with the height of luxury for a long time; from Cleopatra’s milk and pearls concoction to Countess Bathory’s penchant for virgin’s blood.

What the classic image of a luxuriating beauty fails to convey is that baths can also be rather more bother than they’re worth. The water’s too hot, or it’s too cold, or the surface chills before the depths; the tub is too small, leaving knees and shoulders exposed, and the oils and unguents leave you needing to shower them off after soaking; or your book falls in, and the heat means that glass of champagne dries you out faster than a towel… Perhaps there’s a knack to it but, whatever the reality is, there’s no doubt that baths are not always as positive a space or as universally enjoyable an experience as we might assume.

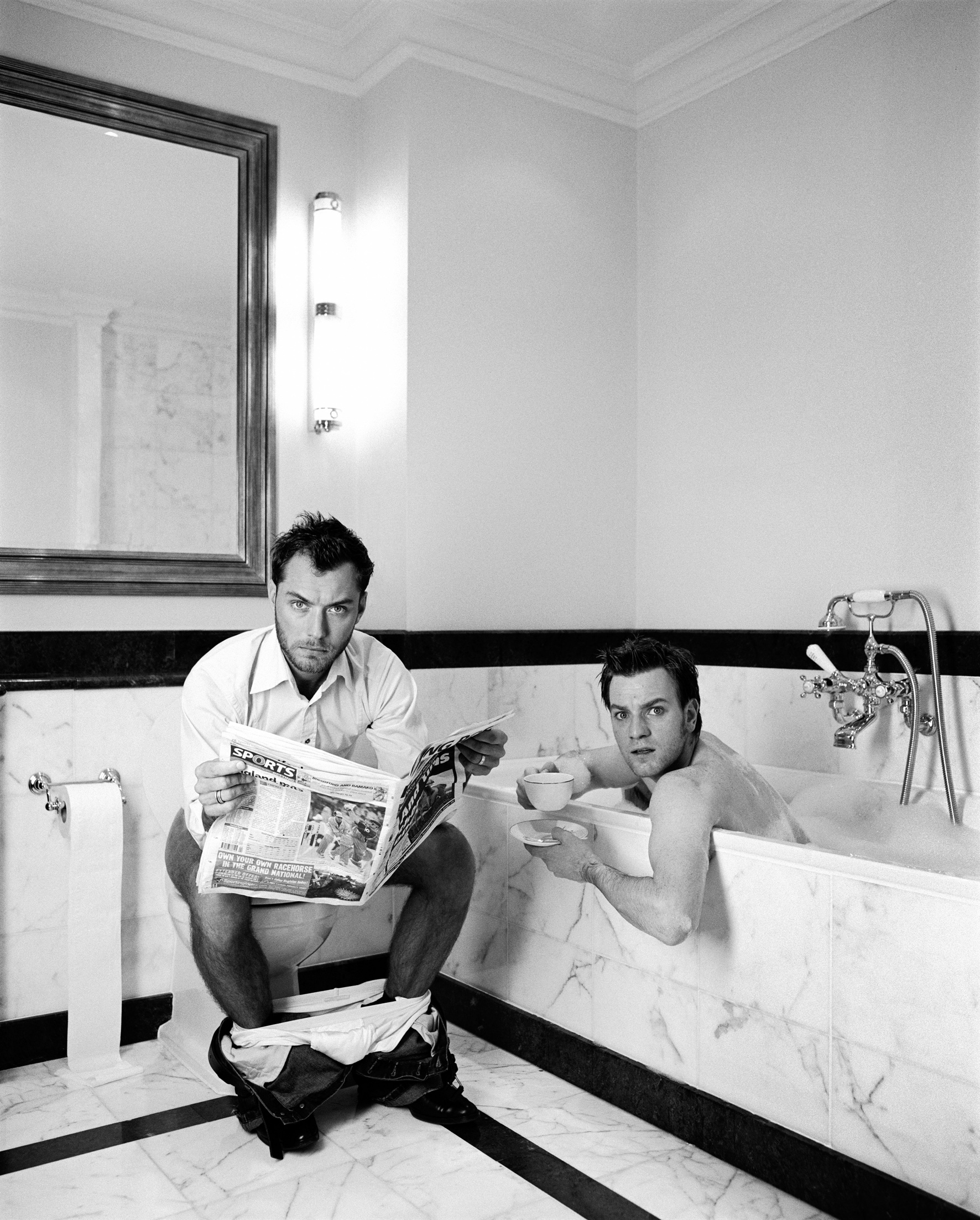

A quick survey of baths in art and visual culture confirms that baths and bathing can be a surprisingly complex subject. From the “celebrity in the bath” shot beloved of photographers like Mick Rock and the late Terry O’Neill, which plays with the exclusivity of fame and the intimacy of a bathroom (not to mention the absurdity of bubbles), to the complex politics of David’s The Death of Marat and George W. Bush’s contentious knees, the bath can be a site of some complicated negotiations between power, luxury, personhood, and vulnerability.

“It takes time to draw a full bath, and time to soak; it takes space and solitude, and control”

Men portrayed in bathtubs tend to be influential and powerful, even in death. Women, however, tend to be either objectified or vulnerable. The combination of nakedness and sensual self-indulgence is an excellent trigger for puritanical instincts. Whether it’s the threat of statutory rape underlying all those red rose petals in Sam Mendes’s American Beauty (1999), or the fate of any female character who’s ever been dragged under her bathwater by unknown forces in a horror movie, popular culture delights in violence against women attempting to relax.

Juno Calypso’s series The Honeymoon subverts this trend. In her world the women who occupy the (pink and heart-shaped) bathtub are unabashed, reclaiming aspects of the horror

-movie monster or the voyeur, and subverting the expectations created by films and fantasy. A hand reaches up, zombie like, from a pool of pink liquid; it grips the edge of the tub, preparing to emerge. Faces are covered in cosmetic aids reminiscent of Michael Myers’s hockey mask. Her bathers fight back.

Vulnerability and power are omnipresent themes in Nan Goldin’s work, where her queer, intensely alive subjects make their power in their own image. Her staggeringly intimate work often features individuals and couples in bathtubs, defiant and bonily androgynous, making out or tripping out. The privacy of the bathtub is prime territory for Goldin, allowing her to demonstrate her unparalleled ability to be absent; she gives us images documentarian in their honesty and poetic in their impossibility.

The ability to disappear behind the camera is one shared by Chloe Dewe Mathews, whose wind-stripped photographs of the lands around the Caspian Sea are marked by a profound emptiness. Mathews’s photographs bring the elemental nature of baths and bathing to the fore by exploring how “oil, fire, uranium, and water are integral to the mystical, economic, artistic, religious, and therapeutic aspects of daily life” in the lands around the Caspian Sea. Some of the most striking photographs in the series are of bathers, soaking in crude oil, or in Iranian hot springs said to have the highest levels of naturally occurring radiation in the world.

“From books to iPads to sheet masks, champagne and fast food, there seems to be a lot you can do in a bath, depending on personal preference”

These image spark high levels of dissonance for those of us who have been raised to think of these elements are dirty, destructive, and detrimental to the health and wellbeing of individuals and the planet, but also reveal a universal concern with self-care, a concern which has had bathing at its heart for centuries. They also reflect back to us our unthinking acceptance of water’s cleanliness, innocence, and abundance—an assumption increasingly under threat as worldwide droughts, algae blooms, pollution and acidification threaten the world’s fresh water supply. Soon baths may be even more of a luxury than we thought they could be.

- Left: Chloe Dewe Matthews, Albina Visilova (a regular visitor to the Naftalan Sanatorium), Azerbaijan, 2010. Right: A young woman bathes in crude oil at the sanatorium town of Naftalan, Azerbaijan, 2010

Water usage, voyeurism and political propaganda aside, the bath as a space and as an activity isn’t necessarily devoid of stress, no matter who’s in it or what their bathing in. From books to iPads to sheet masks, champagne and fast food, there seems to be a lot you can do in a bath, depending on personal preference. The surreal, dioramic photographs constructed by Aleia Murawski and Alex Wallbaum play with the idea of a “dream” bath, creating visions of sensory overload in plastic and steam and glorious rear-projected sunsets. These fantastical bathtubs are both attractive and repellent; as much as you might want to dive into the glossy, kitsch, overwhelming world, they also have an edge of oppressive mania—the experience is akin to lucid dreaming. These images cover almost every angle on bathing at once, with toy soldiers and selfie sticks and Nair hair removal cream and roses and Cheetos all emerging invitingly and worryingly from the steam.

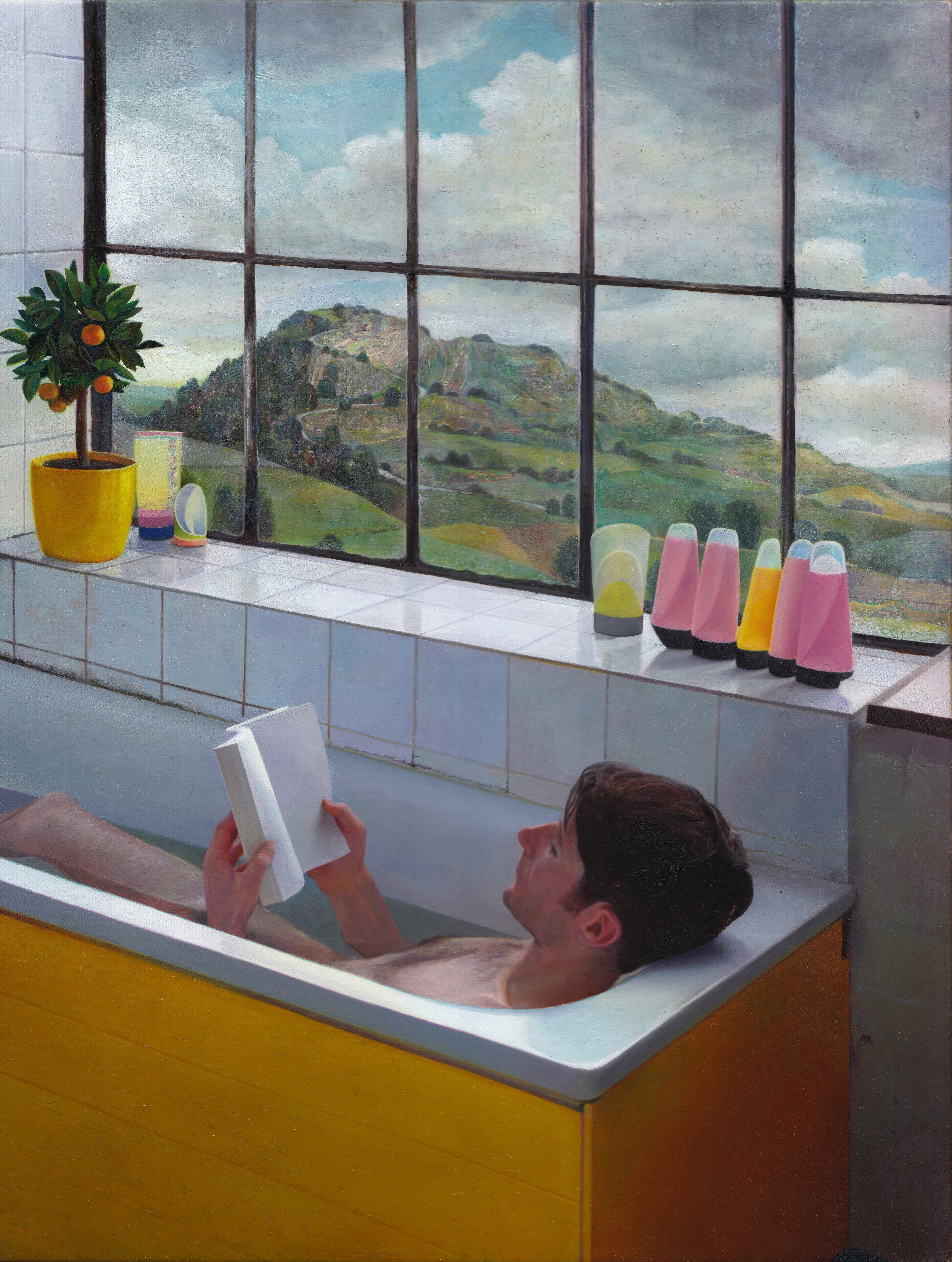

There are, in fact, surprisingly few truly relaxing images of baths and bathing in contemporary art and visual culture. One take on the theme is Gareth Cadwallader’s Bath (2016), a painting which blends the flat, beatific light of Renaissance religious paintings with a hint of surreality. It looks appealing, but fundamentally unrealisable. Perhaps a truly calm bathing experience can only be achieved in dreams, or in miraculous times. Even in this calmest of works, there is the faintest manic edge to the scene in the overabundance of identical products on the sill. The ineffable appeal of the bathtub remains intact, and the reality is still complicated.