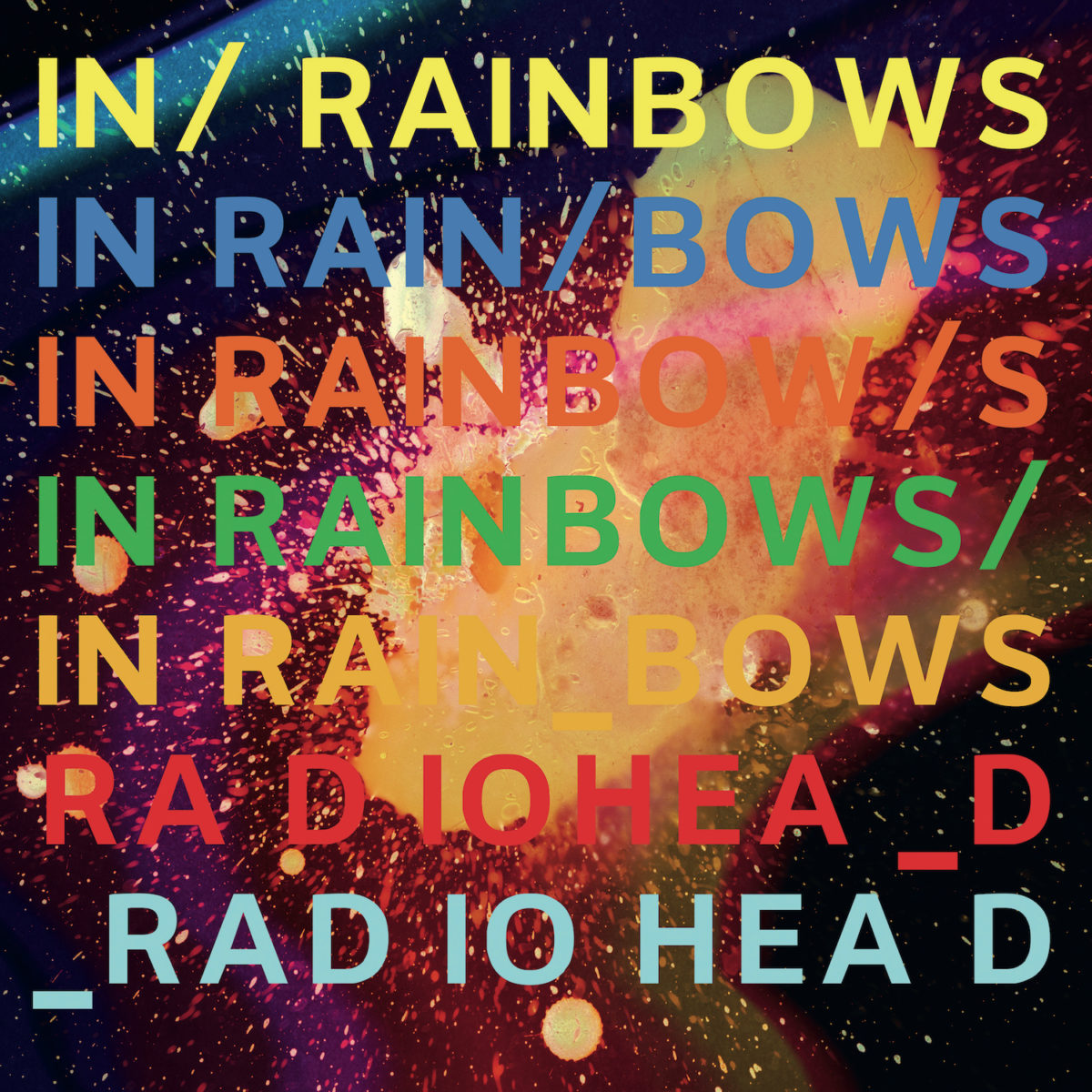

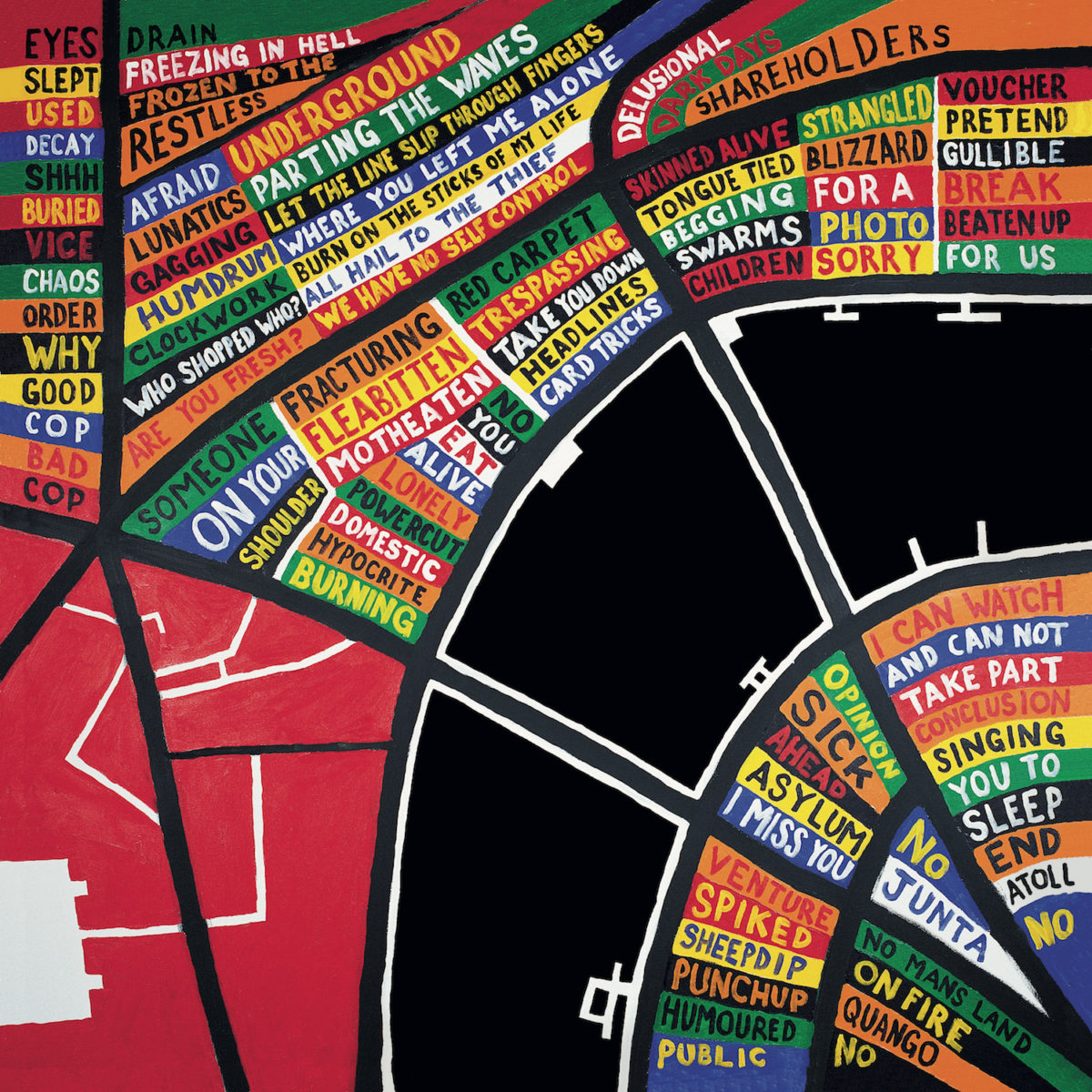

Stanley Donwood’s work for Radiohead feels as chilling, arresting and—most terrifyingly—relevant today as it ever did. In the twenty-five years he’s worked with the band, the artwork has shifted dramatically with each release in terms of its aesthetic, process and story, but a few constants remain. For one, even when bold colours and friendly hand-lettering are deployed (such as the sleeve for In Rainbows), there’s always an underlying sense of disquiet—an unease that beautifully augments the band’s ever-shifting sounds. As with all the best art/music collaborations, Donwood’s visuals are inseparable from the sounds. He gives listeners not only a richer sense of escapism but a way of explaining, or at least discussing, the strangeness inherent in what it means to be alive.

Whether with Radiohead, or across projects like his ongoing work for Glastonbury, the linocut graphic novel Bad Island, JG Ballard book covers or large-scale installation, his work is frequently disquieting, and frightening even. But Donwood himself is calming and very funny, in that particularly dry, English way. You can sense this from his recent book, There Will Be No Quiet. A curious combination of monograph, a wryly comical humoured autobiography, the hefty tome showcases some of Donwood’s best known projects and the fascinating, often perplexingly labour-intensive processes behind them.

“I’m literally watching paint dry,” he says as we start chatting. This isn’t an unusual thing for the artist: he’s an advocate of taking a five to ten minute “sitting-and-looking” break every half-hour, to, well, watch the paint dry. “I used to smoke rollies,” he says, “so I’d do that and put a record on, and [one track] is about the right amount of time. If I just carry on and on, when I do stop, I realize what I should have done long before, and have a think about what I was doing.”

For someone whose work is so visible, and has proven both profound and prophetic over the years, Donwood reassuringly seems to grapple with the same struggles we all do—even if he mixes things up more than most when it comes to medium and method. “I’ll do anything to avoid working really, like washing up, hoovering, tidying up that I would never do otherwise… arranging things that don’t need arranging. Eventually i’ve got to give in and do it, and deadlines are a bit of a help to be honest,” he says.

“I’ll do anything to avoid working really, like washing up, hoovering, tidying up that I would never do otherwise…”

His projects each seem to use an entirely different process from their predecessors: The Bends cover, showing a pallid, orange figure with mouth agape, saw Donwood use VCR cassettes to film a CPR mannequin, then photograph the footage; OK Computer’s cover was designed to the self-imposed rule that nothing could be erased.

In writing the lyrics for Hail to the Thief, Radiohead lead singer Thom Yorke used the cut-up technique pioneered by the surrealists, and later by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin in the 1950s, as well as David Bowie—cutting texts and placing individual words into a top hat. These were reassembled to form a new set of lyrics. “It was really interesting,” says Donwood. “It completely transformed what he’d written into something else, which worked better visually to me with the sound of the album.”

The pair met as art students at the University of Exeter, and Donwood has created all of the band’s artwork since 1994 single My Iron Lung’s cover. It was around this point that the artist adopted his pseudonym (Stanley Donwood isn’t his real name, and he and frontman Thom Yorke frequently dabble with new monikers on various albums—Zachariah Wildwood, for instance, was pinched from a gravestone somewhere in Sheffield).

“It’s not really my cup of tea, because of all the guitars and things. I was really into techno back then”

The pseudonym began when Donwood first started working with Radiohead, when he’d just had his first daughter and wanted to separate his private from professional life. “On the one hand, I was like any new father: a mixture of extremely proud, scared and full of trepidation and wonder—there was also the reality of clearing up sick and shit. On the other hand, I was working on artwork for what was already quite a well-known band—but not really my cup of tea, because of all the guitars and things. I was really into techno back then.”

In his work with Radiohead, artwork deadlines are dictated by the band’s process: the artist usually joins them wherever they’re recording, creating the artwork concurrently with the band as they work out and realize the album’s sounds. “We work quite closely; and so the deadline feels like a fluid fixed point—you know it’s there, but at the start you’ve just got a vague idea,” says Donwood.

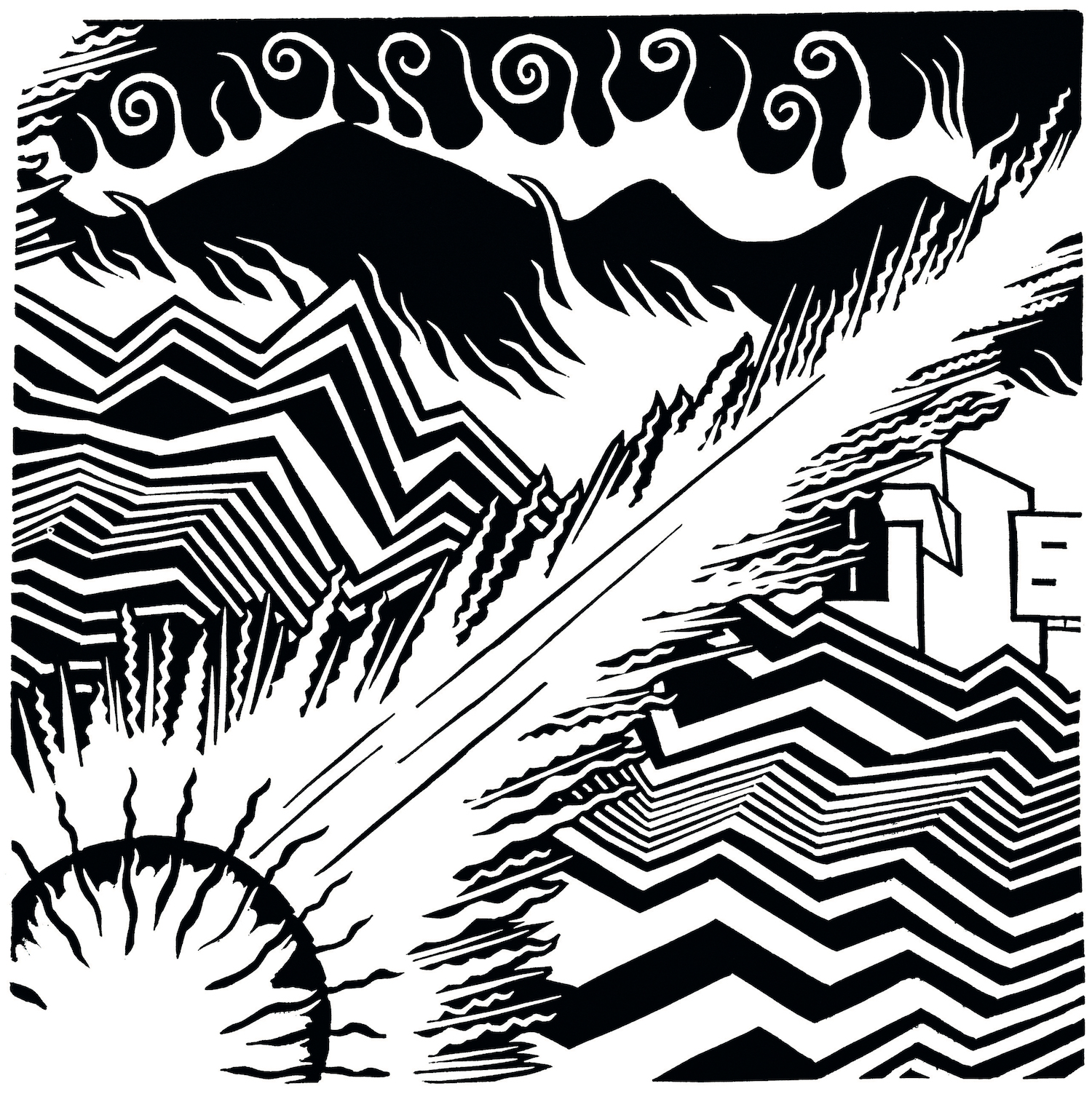

“I often end up working with them for quite a long time during recording or while they’re making the music, and working out what it will be, finding its shape. I’m listening, and trying to see what the record ‘looks like’, and what sort of approach I could take.” Such narratives, though, are never obvious, as evidenced in the likes of art work for Kid A—a personal favourite of mine, and also of Donwood’s. “I look back at Kid A and Amnesiac as a sort of twisted triumph because it felt like wrestling something out of what was a horrible, difficult situation and time for a lot of people, for many reasons. But we managed to get something out of that: when Kid A came out I played it to my mates all night… I was kind of obsessed with it by then.”

But how have band and artist alike retained such a spirit of innovation, and apparent friendship, throughout their quarter-century-long collaboration? “I don’t know…” Donwood ponders. “I’m the opposite of volatile, maybe, I’m just really easygoing. Life’s too short for petty interpersonal disagreements about nothing.” He adds that he’s appreciative of second opinions—even negative ones. “If they’ve got criticism, I quite like it, because I know if I’m just left to myself I become terribly self indulgent and make work which means nothing to anyone except me.

“Sometimes when I’ve done stuff on my own, people hate it. It’s usually really gloomy”

“I really want to make work that people like; when I do that, it’s much more colourful and cheerful. When you’re doing artwork for book or record covers, you want people to buy it—they have to pick it up. Sometimes when I’ve done stuff on my own, people hate it. It’s usually really gloomy, really dark, quite monochrome with a lot of black… it looks like work by someone you might be worried about.”

While his Radiohead art has proven very well-liked indeed;, you could also argue that it falls into the “someone you’re a bit worried about” territory. Donwood decides to open and close his new book with frank discussions about his mother’s death. Within the pages, he nonchalantly describes experiences that sound at best profound, at worst, thoroughly harrowing.

There are terrifying recurring nightmares about demons, with motifs like “bloodstained wicker baskets filled with severed heads”, and a certainty that if he died in his dream then he would in real life. To combat these visions, he began writing down his dreams making them into pamphlets to send to friends, which helped. He also describes chronic lingering fears around nuclear power and weapons, and a feeling of “utter hopelessness about the human situation at the beginning of the twenty-first century”. He then swiftly negates such statements with surrealist-leaning references to Dolly the cloned sheep or other tangents.

One of his overarching goals, achieved beautifully in his conversational, but never patronizing writing style, was to create the sort of book that he’d have found useful as an art student: “something that was sort of more honest”, as opposed to slick monographs of artists so well established, or dead, that their careers seem utterly unrelatable. “I wanted to show all the things that can go wrong: all the difficulties of making an artwork, which is a lot more real than ‘just get a canvas, stick some paint on it, it’ll been brilliant’. It’s not like that at all.”

Writing the book seems to have been a tricky but ultimately cathartic process. To complete it, Donwood organised of an array of outmoded digital recorded media, such as zip disks, CDs and SyQuest discs. “The action of sorting it out was like a coded diary, in picture form. Once I saw the order the projects had been made in, I could remember everything that went with them and how they happened.” He adds, “Writing that book was a kind of psychological journey of self discovery in a way, or a personal archaeology, scraping away and finding all this stuff I’d totally forgotten or blocked out for reasons of psychic survival…”

“Anything horrible inside my brain hasn’t got long enough to cause any damage before it’s squeezed out”

For all this talk of demons, nightmares, “psychic survival” and so on, Donwood says that the great thing about the fact he’s always busy, “usually either making artwork or writing or something”, means that he reckons he’s probably the most well-adjusted person he knows: “Anything horrible inside my brain hasn’t got long enough to cause any damage before its squeezed out.”