It’s natural to see food as a good thing. Eating is enjoyable and it keeps you alive. But we have increasing doubts about the state of the food industry today: how well should we eat; and how much; and, increasingly, at what cost to the world? That leaves plenty of scope for artists to pick up on. How sweet, some ask, is too sweet? Is there poison in the system? Could meat be healthier? Might agriculture itself be a mistake? Guilt and conscience isn’t necessarily the tastiest option, but perhaps it’s the more nourishing path.

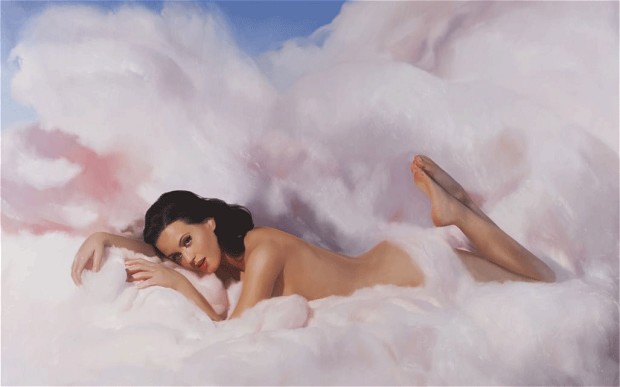

Will Cotton

American painter Will Cotton satirizes indulgence in his world of ill-chosen food, with landscapes made of candy and models parading their sweetness. That fits with singer Katy Perry’s aesthetic, and she asked him to collaborate on the video for her single California Gurls. Not only did he do that, making some kind of reality of his fantasy world, he then used the video as a source to make paintings about how his own paintings came to life. That circularity stands in nicely for how hard it can be to escape the cycle of our unhealthy desires.

Mai-Thu Perret

Nutritionally, apples aren’t the obvious example of food being bad for you, but consider the poisonous one offered to Snow White by the wicked witch—a story which carries a trace of the originating bad apple which got us humans expelled from Paradise. Moreover, Mai-Thu Perret’s half-eaten pomes, baked in glazed ceramic, look a little like toffee apples. They’re not healthy on any level.

Roxana Halls

If “you are what you eat” then it will be your childhood consumption which defines you. Roxana Halls’ self-portrait, from a wider practice which questions how gender and class norms circumscribe our choices, calls attention to the food from her youth. Halls says she’s very rarely seen such fare in paintings “as though, in contrast to its nostalgic importance to me, it were not considered of sufficient value for examination”. Here, then, she attempts to carve a life from a laden table—it isn’t easy, as the awkwardness of her action testifies.

Kevin Broughton & Fiona Birnie

London-based collaborators Kevin Broughton and Fiona Birnie conjured up a “dream America” in ten paintings from 2014–15. Their garden of processed meat wittily emphasizes how unnatural the suburban can be, while also blurring the line between animal and plant life. If sausages grew like this, I guess everyone would be vegetarian. Let’s hope they’d contain less saturated fat than the conventionally-farmed version.

Alistair Mackie

Medieval reapers believed that the last sheaf of corn standing contained a dangerous spirit, so they fashioned it into an effigy to be kept safe—in propitiation—throughout the winter. Alastair Mackie had such a sheaf plaited into a traditional spiral, then encapsulated—and, presumably, transmigrated—the spirit implied in bronze. With supplies of the critical food source of wheat threatened by climate change and population-fuelled growth in demand, the gesture has an uncomfortable relevance for today.

Gareth Cadwallader

Gareth Cadwallader has a curious way of painting intimately-scaled, hyper-realistic representations of unrealistically structured vegetation. Against these backdrops his characters play out such everyday rituals as selecting an orange with enough intensity to suggest they are symbolic—but of what? Perhaps this refers to Roelof Louw’s Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges), 1967, which was reshown at Tate Britain in 2016: a stack of some 6,000 oranges replaced on a rolling basis as visitors took part by “consuming” the work.

Paulette Tavormina

The still life of fruit is the most resonant image of food in classical art. So here is one—or, rather, not—from the one-time food and prop stylist Paulette Tavormina, who expertly recreates arrangements typical of the genre in her New York studio, then captures them as photographs in a sort of reversal of photorealist painting. These plums are arranged in the manner of Giovanna Garzoni (1600–1670), an Italian famed for the meticulous realism of her botanical compositions, which typically featured a single insect. She’s of additional interest as one of the few women able to break through with her art career at the time.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 39

BUY NOW