During this time of social-distancing, it feels harder than ever to forbid ourselves the brain-anaesthetizing comfort of the mindless social media scroll. However, bereft of the usual photo evidence of friend-filled pub trips, weekend getaways and companionable coffee shop snaps, our feeds are looking a little different these days. As we follow government

protocol and remain inside, the photographic focus has also turned inward, as our friends display the intimate details of their homes, their families and their own faces.

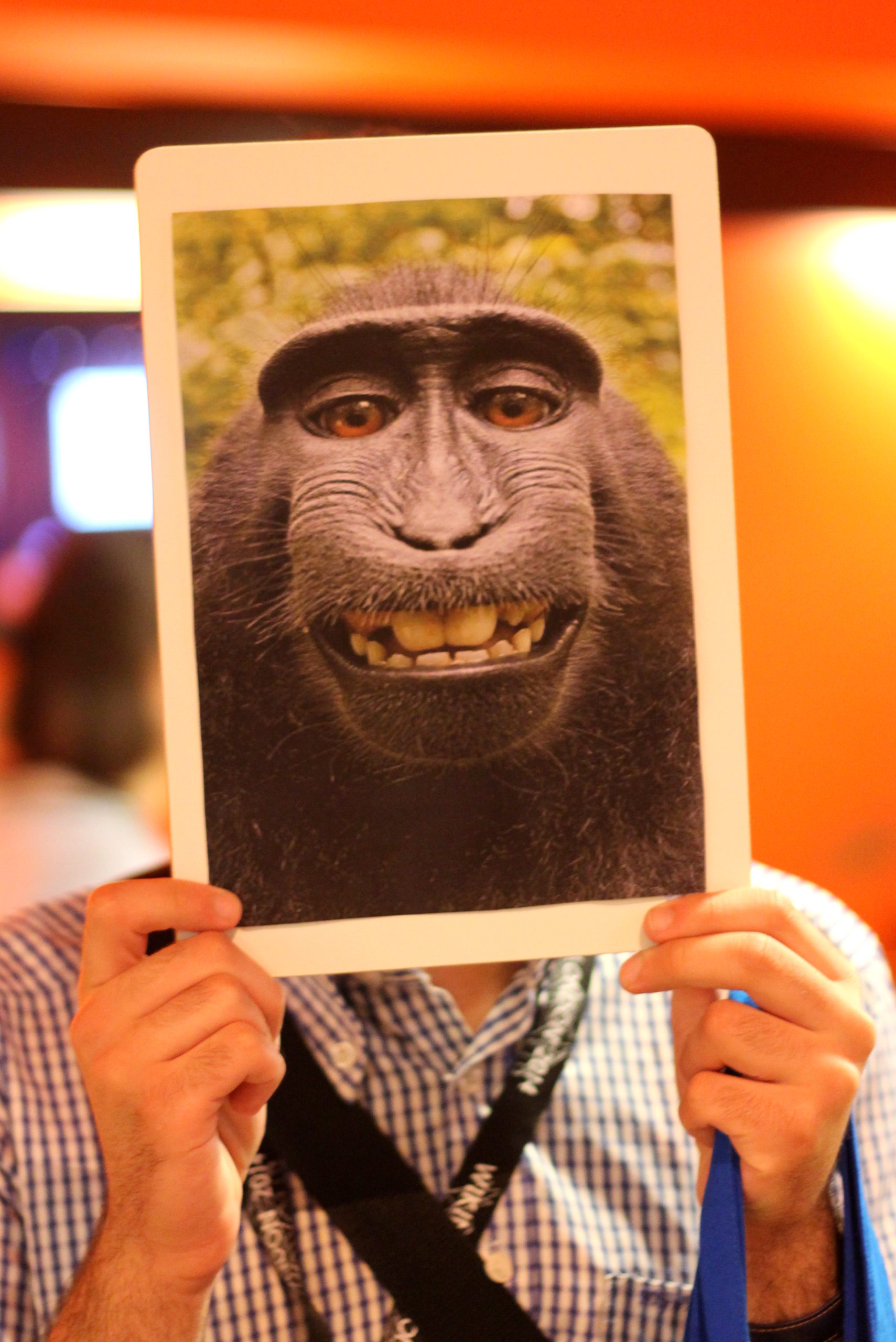

In 2011, before the word “selfie” had even entered our vocabularies, the world went mad over one face in particular. Described by UK newspapers as the “first monkey self-portrait”, photographs of Indonesian crested macaques were released by British nature photographer David Slater to resounding enthusiasm and hilarity from the public.

Slater’s intention had been to capture images that drew attention to the unique personalities of these creatures, promoting the connection they held to the human species and thereby provoking action in altering their endangered status. Relishing the hype that surrounded the absurd hilarity of a monkey self-portrait, Slater downplayed his own role in the photos’ creation.

Making light of the days he had spent tracking the monkeys and letting them become familiar with his presence, Slater allowed the media to have some fun with the story. Newspapers were happy to overlook the time Slater had spent experimenting with different methods of capturing the creatures up close, and ran instead with amusing narratives of mischievous monkeys scampering off with camera equipment and taking self-indulgent snaps.

However, Slater’s all-too-convincing narratives resulted in a sad self-sabotage. Later that year, the photos were uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, a site which hosts photos deemed to be in the public domain and therefore available for public use sans copyright charges. The reasoning was that the photos were taken by the monkeys; since copyright cannot be granted to animals, they belonged to nobody. And therefore, they were the property of everybody.

“When we’re looking for connection, how much of ourselves are we signing away?

But this wasn’t the end of it. Animals rights group PETA then sued Slater, taking him to court for what they saw as an attempt to wrest the rightful ownership of the photographs from the monkey, whom they identified as the six-year old male Naruto. Although, to make things even more complicated, there was further debate about whether they’d even got the right monkey. PETA lost that cause, which did at least prevent the absurdity of the technicalities of assigning royalties to a monkey.

But this is not the only absurd situation which highlights the ambiguity of possession in our digital world. In 2017, Manchester-based public WiFi company Purple listed in their terms and conditions that those who signed up bound themselves to 1000 hours of community service; in 2014, cybersecurity firm F-Secure offered free wifi in exchange for the user’s first-born child; in 2010, the entertainment company GameStation added a clause to the end of all their online purchase conditions that required the consumer to “agree to surrender their immortal soul” to the company.

While these examples are obviously tongue-in-cheek, they nonetheless challenge us think about just how much we’re willing to give up in aid of our digital reliance. During social isolation, as everyone resorts to Whatsapp video, Zoom, and Houseparty for their communication, these questions become even more pertinent. Use of WhatsApp is up 40 per cent worldwide, and while Zoom had 10 million daily users in February of this year, in March it saw 200 million daily users.

“In life after lockdown, a greater surrender of personal details may be part of the new normal”

The continued connection that these programs promise is not without its peril. While the widely circulated claims that Houseparty mines data and sells it on to third parties has been dismissed as false, Zoom have admitted that their app has fallen prey to security and privacy issues, and an old hacking scam on WhatsApp has resurged, making the most of the increase in the app’s usage. When we’re looking for connection, how much of ourselves are we signing away?

But information given willingly or unwittingly over the internet is not the only form of increased surveillance that we are witnessing. Telecom companies across Europe have released data which reveals people’s movement around cities, and wristband trackers in South Asia are being used to monitor those with whom the wearer came into contact. In Russia, facial recognition technology in CCTV is used to enforce social distancing, and in India geolocated selfies are used to prove that self-isolation techniques are being upheld.

Perhaps these are necessary uses of personal information in a strange and unprecedented situation. However, as we begin to contemplate how life will be different when this is all over, it is somewhat alarming to consider that a greater surrender of personal details may be part of the new normal. Just as that monkey staring grinning at his reflection in a camera lens had no prescience of the ramifications of his actions, we have no idea what our future will look like.