Drag has always formed a significant, if unsettled, presence in Western pop culture. Over the decades it has represented a multitude of possibilities: as an escapist expression in times of conflict; a bawdy light entertainment staple (1970s comedy flirted obsessively with the male in female guise); as glamour, LGBTQ sexual liberation, confrontation and more.

Drag has pulsed throughout the music that made a bold impression on me: acts like Bowie, Eurythmics (not just in the blurred gender dynamics of early eighties videos like Love Is a Stranger and Who’s That Girl, but also throughout their wonderful 1987 concept album/films Savage), and John Waters‘s actor/hi-NRG star Divine (who terrified my childhood self when I first saw him on Top of the Pops; I grew up to adore him). By the time I was a young music journalist in the late nineties, it was still clear that drag was a daring statement; when Brit singer-songwriter Kevin Rowland unexpectedly dragged up in red lipstick and negligee for his 1999 album My Beauty, he was brutally maligned by the mainstream—and bottled off stage at Reading Festival.

“By the time I was a young music journalist in the late nineties, it was still clear that drag was a daring statement”

If a new “generation mainstream” has since appeared to redress its own issues and idiocies, then credit is surely due to the enduring fearless force of drag artists and performers. The Hayward Gallery’s new show Drag: Self-Portraits and Body Politics certainly emerges at a transformative point for drag culture; smash hit US TV series RuPaul’s Drag Race has propelled drag into prime-time realms; drag imagery and slang (“fierce”; “Yasssss!”; “sipping tea” etc) pervades social media; DragWorld, billed as Europe’s biggest drag convention, took place in London last weekend. And drag keeps giving music and club scenes life; one of 2018’s most thrilling music highlights come from Christine and the Queens, with French singer-songwriter/choreographer Héloïse Letissier restyling herself as a boyish heartthrob for her latest material.

This exhibition is conscious of the current vogue for its theme, but also very sensitive to its legacy. When I spoke to the Hayward Gallery’s curator Vincent Honoré a few weeks ago, he explained: “Drag is not only a way to resist; it reflects the resistance of our crisis of identity… Thinking about the herstory of drag, I really wanted a polyphony of voices and expressions.”

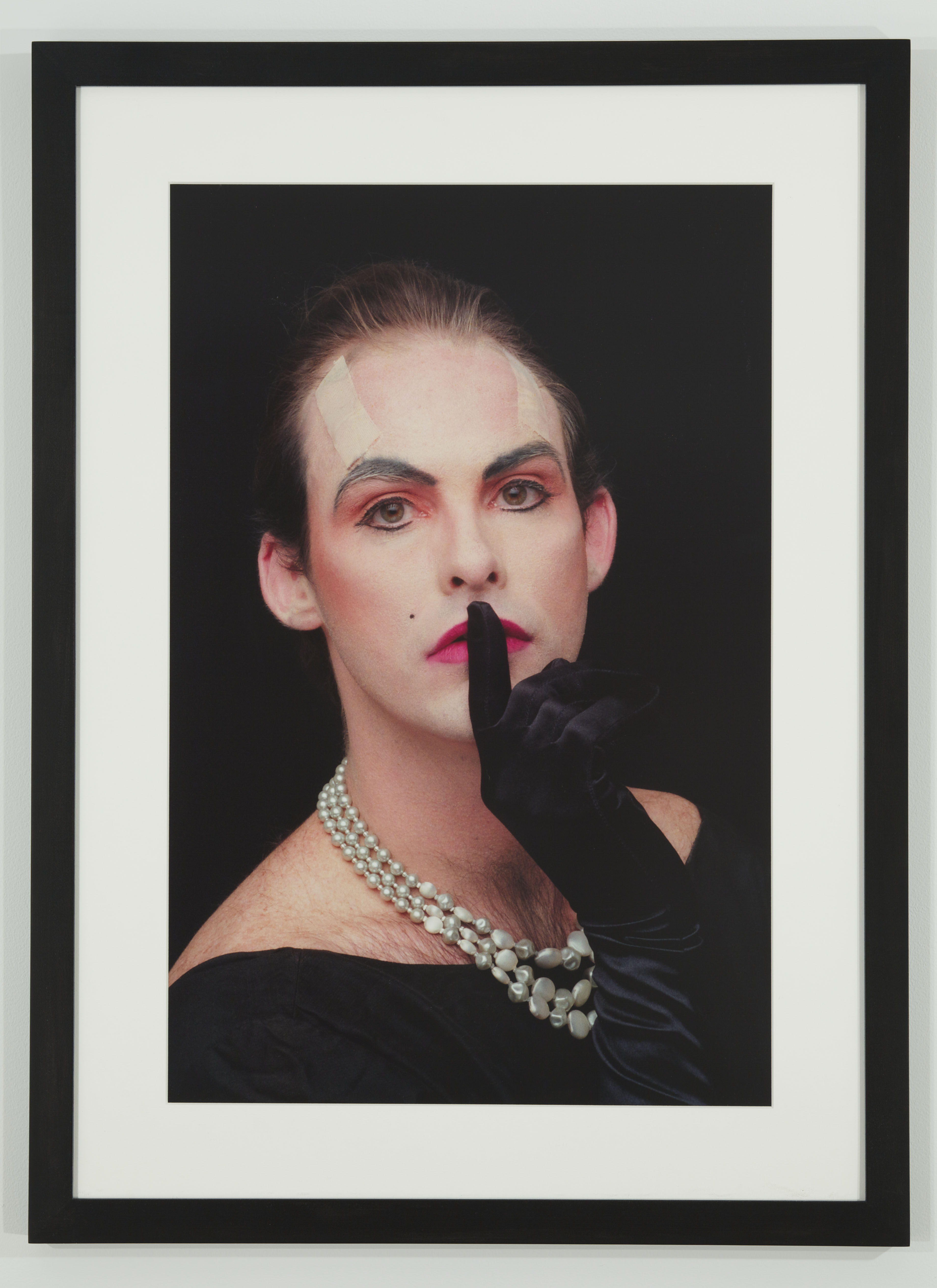

The show is surprisingly compact, contained within the Heni Project Space rather than the full Hayward Gallery levels; this decision feels slightly tentative, as the theme could have easily extended throughout the latter spaces. But if Drag feels like a sampler rather than a fully immersive odyssey, its collection is still impressively multi-layered, thoughtful, provocative and accessible (admission is also free). A series of exhibition tours, led by various drag performers, will take place in September and October. The focus on self-portraits gives a crucially intimate edge; there is a sense of spectacle in many of these works, but it is on each artist’s own terms.

Drag’s non-linear representations span photographs, video installations and paintings; Paul Kindersley’s modern works encompass all of these media, including his take on that contemporary everyday phenomenon: the YouTube

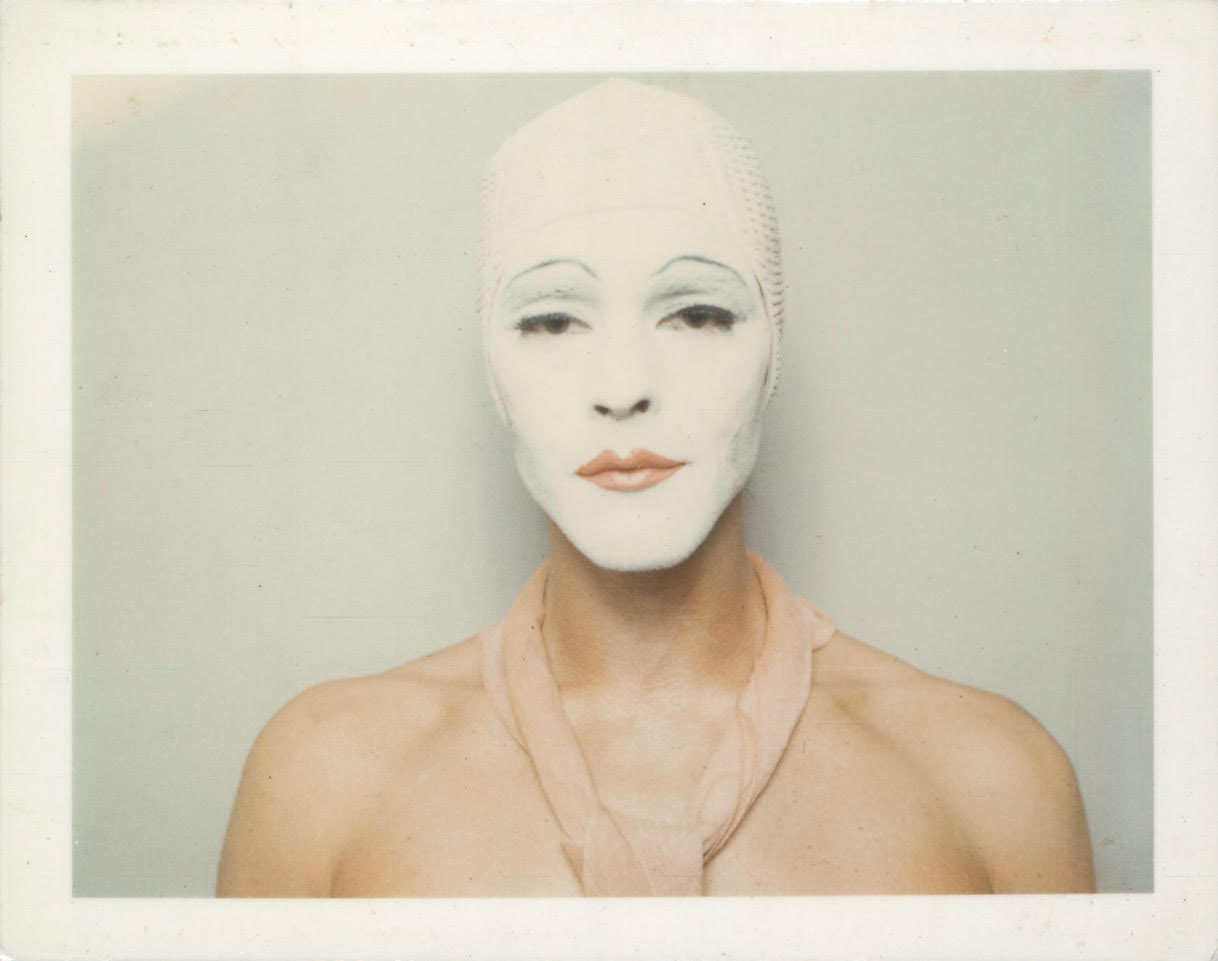

makeup tutorial. There are iconic faces here, and unexpected twists; Robert Mapplethorpe radiates rock star glamourama in his 1980s self-portraits, while Cindy Sherman seems to be eerily peering back at us through the rigid grins and dense makeup of her Headshot alter egos. Meanwhile, Nigerian photographer Samuel Fosso’s 2008 “autoportrait” as the civil rights heroine Angela Davis (taken as part of Fosso’s African Spirits series) presents an instantly recognizable vision of power and beauty, before its sense of identity unravels.

The sense of a double-take is key to Drag; in Oreet Ashery‘s Self Portrait as Marcus Fischer (2000), the artist convincingly appears as an Orthodox Jewish male bearded figure, yet that certainty is disrupted by their hand cupping their female breast, exposed from their shirt. It is a provocative gesture, and not necessarily a sexual one (it brings to mind a mother preparing to breastfeed an unseen infant); we become conscious of how “loaded” body parts become when they denote femininity or masculinity. A different kind of double-take appears in Austrian feminist artist Renate Bertlmann

’s sculpture, Enfants Terribles – Innocenz VI, 2001; what initially appears to be a graceful mannequin’s neck, clad in an exotic velvet gown, transpires to be a diamante-studded dildo.

“There is a sense of spectacle in many of these works, but it is on each artist’s own terms”

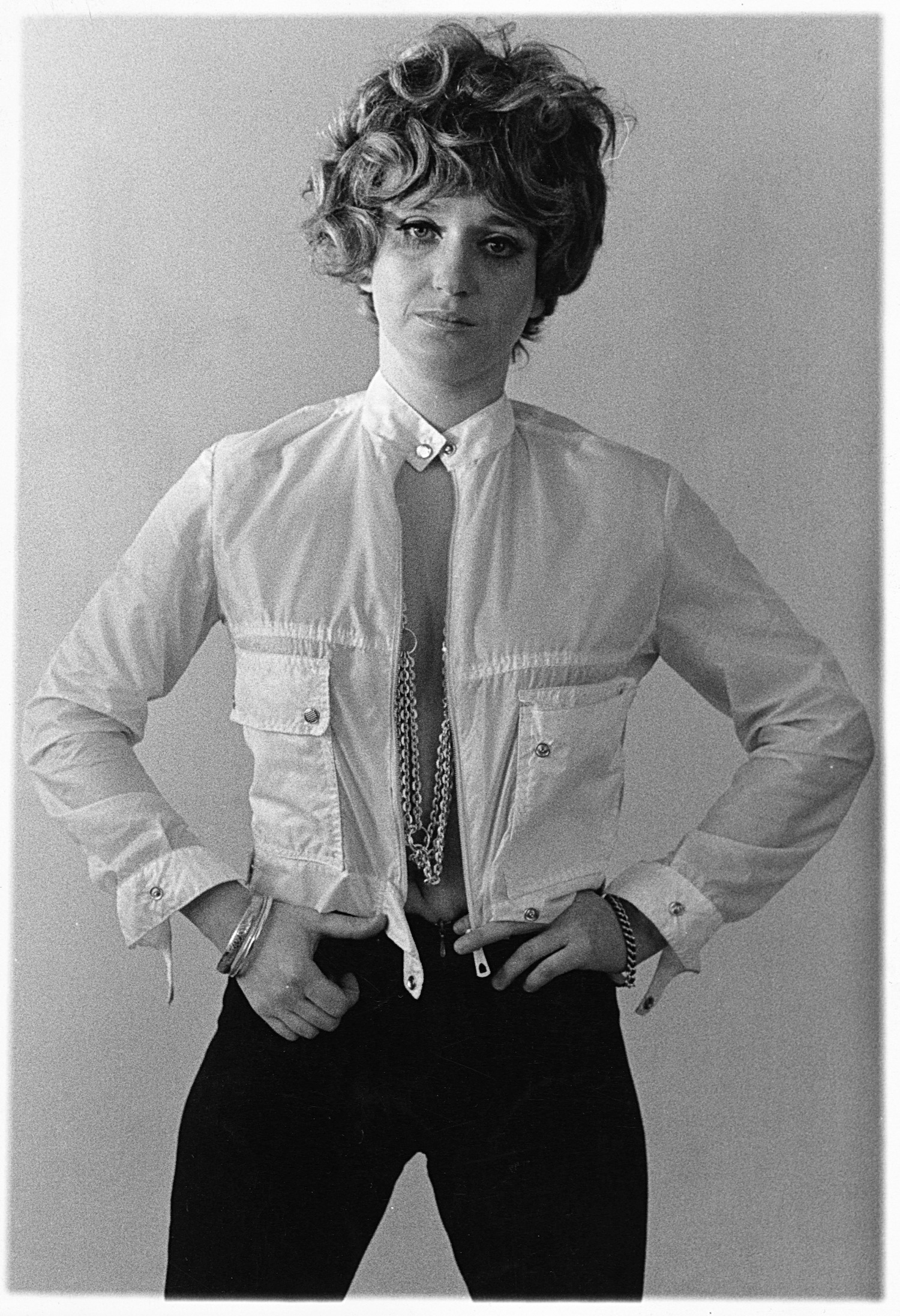

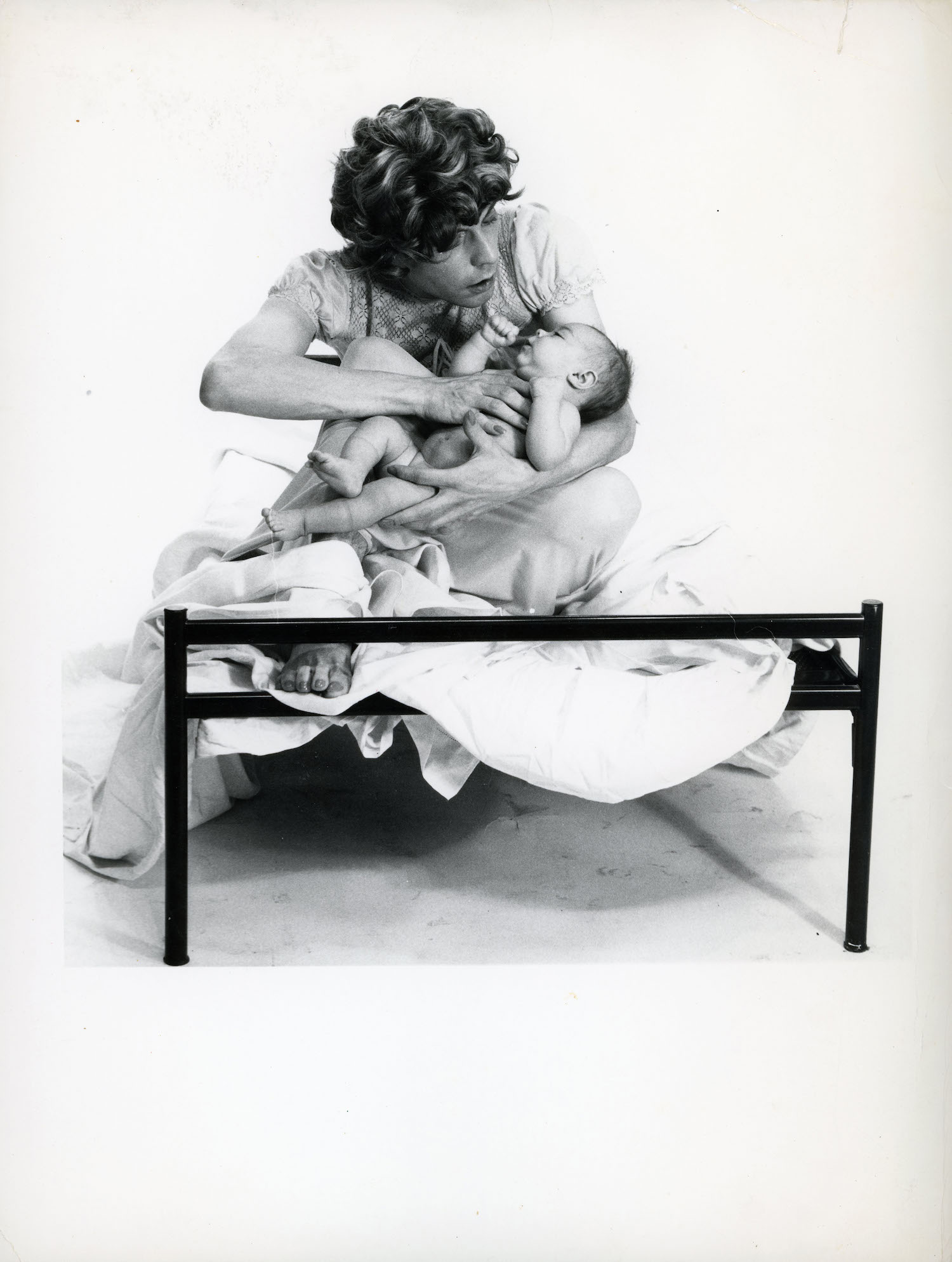

Valie Export’s Identity Transfer triptych of black-and-white photographs (1968) exude a grainy glamour, redolent of that era’s gender-fixated advertising campaigns; the Austrian artist, seen here in androgynous poses—unbuttoned jacket, hands on hips, coquettish smile—took her name from a brand of cigarettes.

Drag’s connections with nightlife take various forms here, including the glitterball scrawl of David Hoyle’s painting on paper, I-Drag! (2016); like Hoyle’s “anti-drag queen” alter-ego The Divine David, it feels brashly expressive yet strangely affecting. The late Leigh Bowery exudes fabulous polka dot poise in Cerith Wyn Evans’s film of his 1988 performance installation at London’s Anthony d’Offay Gallery; Bowery was observed from behind a two-way mirror, and he appears utterly in control of his own image.

“An empathy and humour underpins many of these works; Drag might prove more relatable—or unsettling—than we predict”

There is a sense of freshness that brings together the works from across different decades here. It would have been fascinating to explore a wider array of cultural takes on drag

, however. Standout pieces include the raw intensity of Francesco Copello’s El Mimo y La Bandera (1975): a tiny shot of the Chilean artist, exiled from his homeland during Pinochet’s dictatorship, posing in drag with his national flag. Elsewhere, Ming Wong’s After Chinatown (2012) is a surreal counterpoint to the race and gender stereotypes in Roman Polanski’s 1974 film noir Chinatown, set to a hypnotic subverted version of Jerry Goldsmith’s original movie score.

“There is no gender anymore, it seems; just androgyny,” muses perennially unnerving musician/poet/performance artist Genesis P-Orridge (Throbbing Gristle/Psychic TV), in matronly guise for the video piece Weird Woman (2003). “Love the man and woman inside you… Let Adam and Eve become one.”

Victoria Sin’s We Are Beginning to See (2017) hands us the ephemera of transformation: a lipstick blot, mascara and foundation smeared into a portrait on a facial wipe. An empathy and humour underpins many of these works; Drag might prove more relatable—or unsettling—than we predict, and our personal reactions always speak volumes about our own sense of identity, and what we hope to project. The personal and the political converge most closely here.

“It’s not about man or woman; it’s another way of being human,” says Honoré. As we leave the room, we notice a painting by Kindersley above the door frame: fluid lines forming the shape of two heads and possibly a single body, exuding an independent stance and an inclusive embrace.