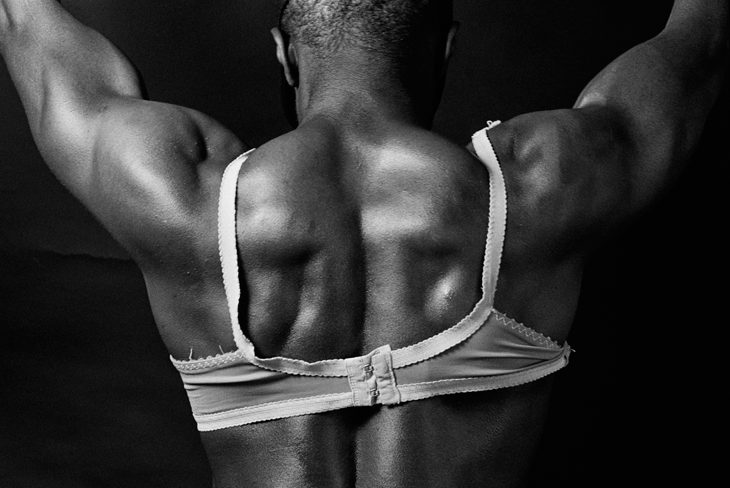

Ajamu X

The sensual, black and white photographs of Ajamu X catch you off-guard. A tender close-up of naked skin; a pair of legs in high-heeled shoes; intimate studio portraits shaped by the idiosyncrasies of desire. Based in Brixton, South London, the artist has spent almost four decades honing his craft, using the camera to explore the power dynamics of pleasure and the Black body in the context of queer activism. These are images of resolute beauty and quiet rebellion. A seminal figure in the British photography scene since the 1990s, with a recent Frieze cover story under his belt, in 2021 he looks set to be introduced to a younger generation through an upcoming exhibition at Cubitt in London, curated by Languid Hands. He will also exhibit at Glasgow International in June, while an artist book, Ajamu: Archive, is also due this year—visit the fundraiser to secure a copy. (Louise Benson)

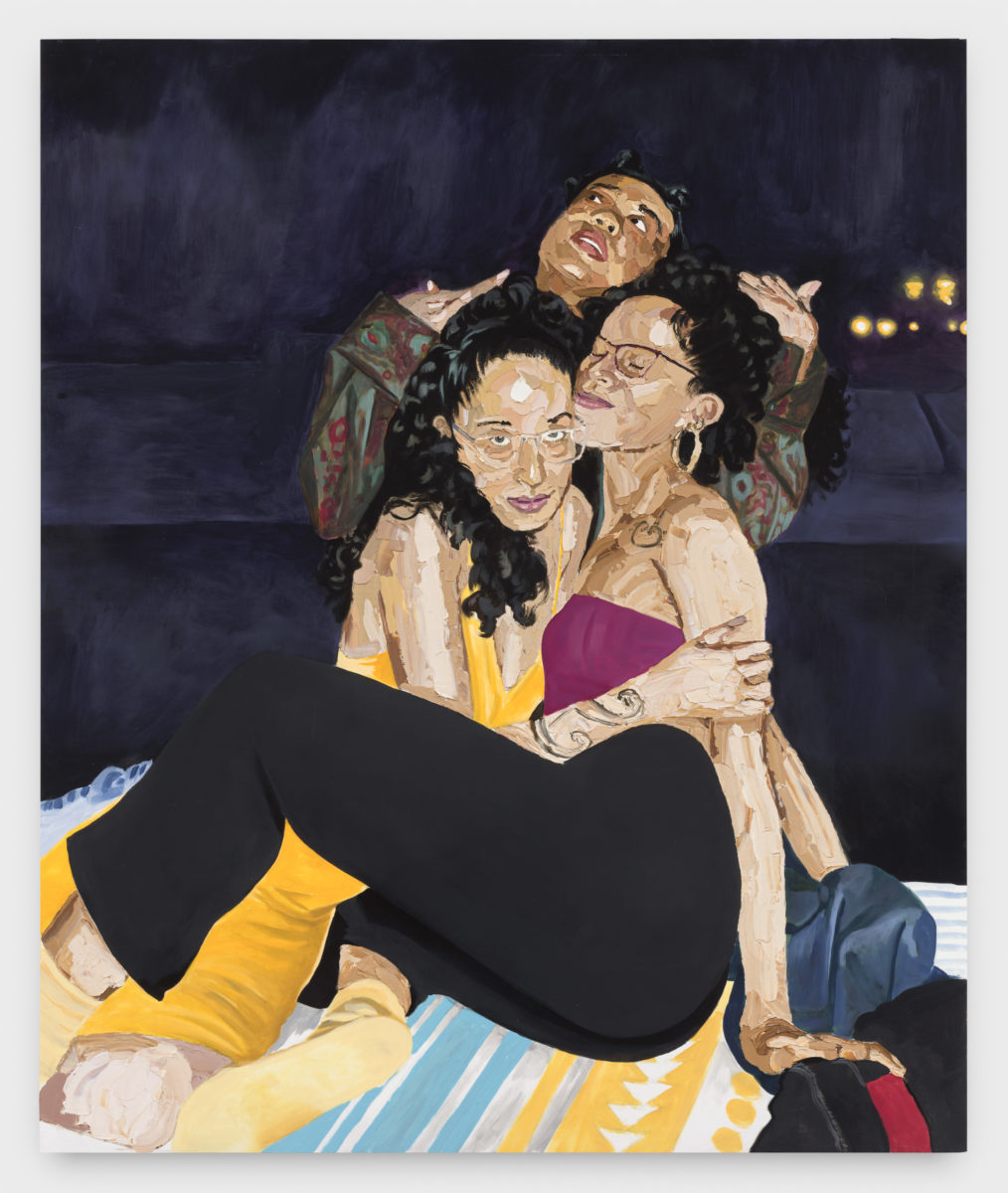

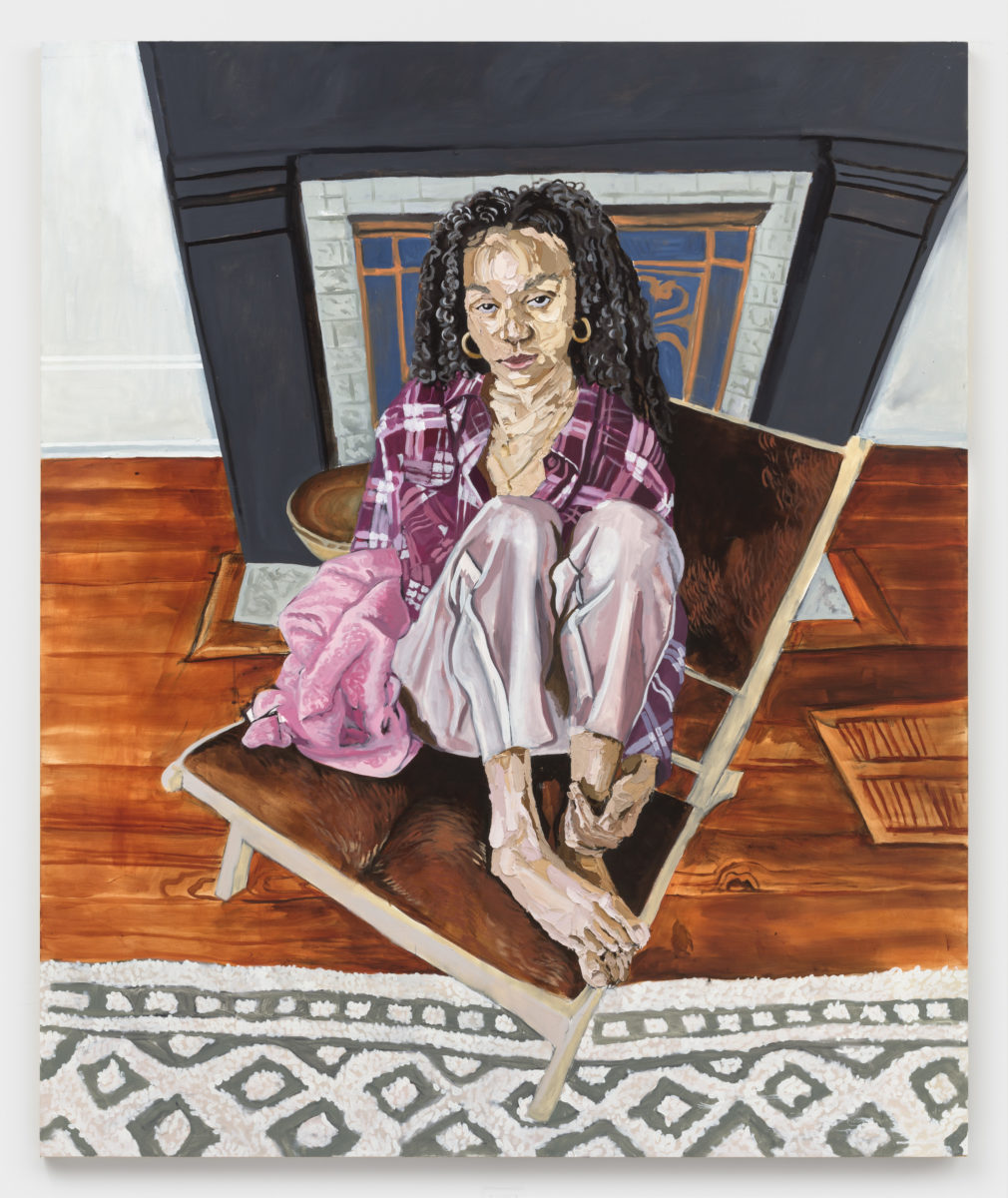

- Gerald Lovell, The Night on the Roof (left), Searcy (right), 2020. Courtesy P.P.O.W

Gerald Lovell

Gerald Lovell’s artworks are textured and painterly, while also capturing the casual intimacy of a photographic snap. The Chicago-born artist has just opened his first solo show in New York, at P.P.O.W. All That I Have focuses on Lovell’s painting as “an act of biography”, and each work is imbued with a personal feel, in which subjects appear to be friends or family, often caught in tender moments and totally at ease in the artist’s presence. There is a sense of closeness in these paintings, in which the viewer takes the place of Lovell and is welcomed in. The artist began painting aged 22, after dropping out of the graphic design programme at the University of West Georgia. He was “frustrated by the codified, academic methods ingrained in formal arts education” and began his painting practice using YouTube tutorials and many of the techniques picked up in previous photographic work. He has said that his interest in photography came from hours spent looking through photo albums at his grandmother’s house. “When I started painting, these were the moments I wanted to represent,” he says. “I find them powerful.” (Emily Steer)

Sutapa Biswas

‘Overlooked’ is the art world’s favourite word, but it’s apt to describe the work of Sutapa Biswas, who hasn’t had a substantial exhibition for 14 years in the UK. Equally overlooked is the Black Arts Movement, active from 1982 in the UK (including artists only recently recognised, such as Lubaina Himid, Sonia Boyce, Claudette Johnson), bringing intersectional identity, feminist and anti-racist concerns to the fore in British visual arts, while experimenting with new ways of seeing. Biswas was born in India and moved to the UK aged four; she studied at Leeds, the Slade and the RCA, and consistently contributed to the movement, with foundational works like Kali (1984) and Housewives with Steak-Knives (1985). However, despite appearances in high-profile institutional group shows in the UK and abroad, Biswas hasn’t had much solo attention. This year, it’ll be impossible to ignore Biswas’ presence: she has a new film, Lumen, premiering at Kettle’s Yard, and an exhibition at Baltic is planned for May 2021. Biswas’ exploration of motherhood is particularly pioneering. I wish I’d had access to her work long ago. (Charlotte Jansen)

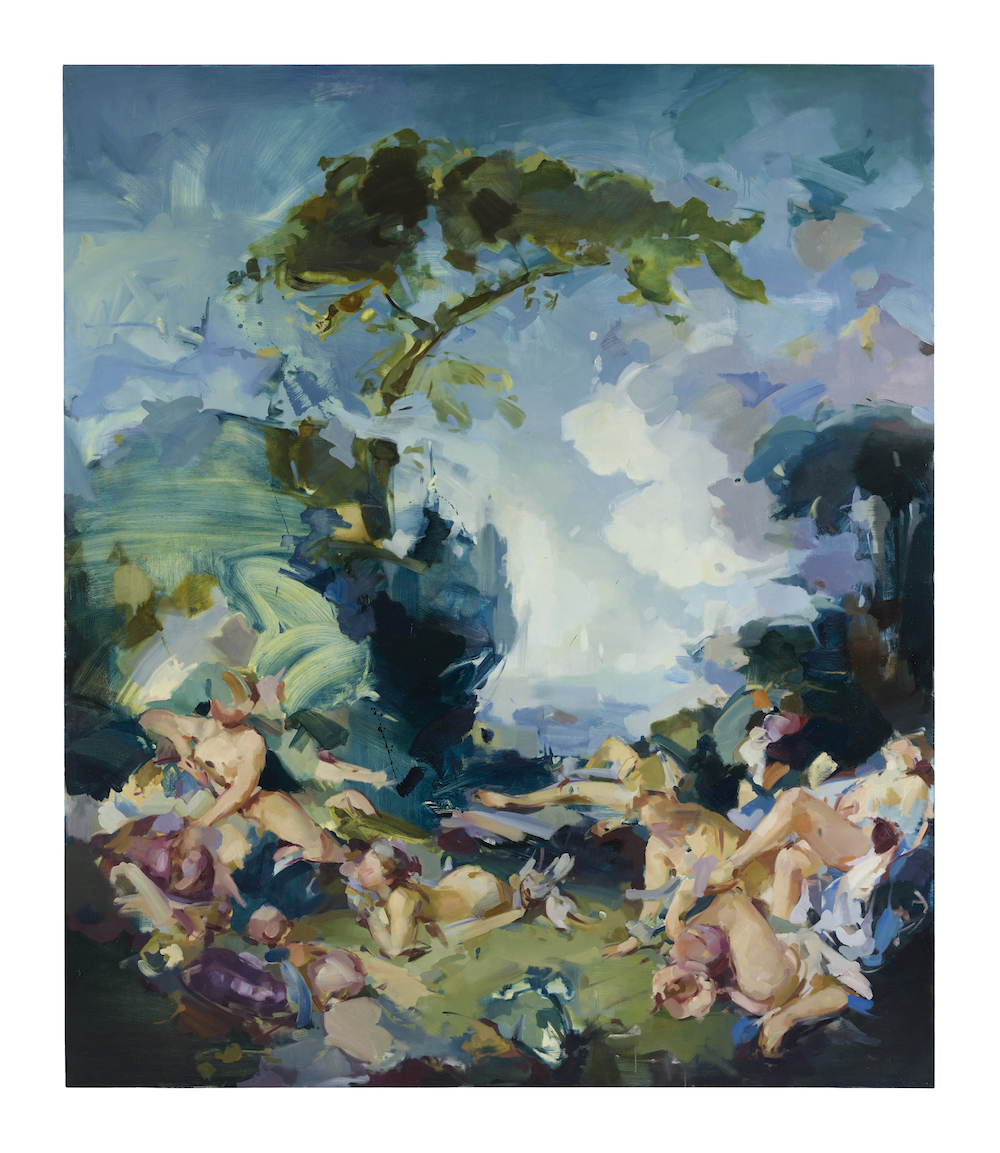

- Flora Yukhnovich, Butter Wouldn't Melt (left); Warm Wet N' Wild (right), 2020. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Flora Yukhnovich

It comes as no surprise that Flora Yukhnovich is in such high demand. The London-based artist creates enormous, vivid paintings that reimagine the luscious (and camp) aesthetics of Boucher, Fragonard and Tiepolo, through expressive, abstracted brushstrokes that can only truly be appreciated in person (as the Elephant team were lucky enough to, during a studio visit last year). At a time when so many of us are confined to our homes, where gathering and revelry are off the table, the artist’s references to heavenly scenes and the fête galante serve as glorious escapism. Following a residency with Victoria Miro in Venice, and a subsequent solo show, Yukhnovich was recently announced as the newest member of the gallery’s roster, with another exhibition expected in its London space next year. (Holly Black)

David Henry Nobody Jr

While David Henry Nobody Jr has been working for some time now, his exploration of the darker sides of American pop culture and politics, and his questioning of ‘the self’ and modern day narcissism, feel more relevant than ever, as we begin another year when our lives are lived more online than off. The artist has made a name for himself through Fluxus-inspired alter-egos, and is a founding member of the five-artist ‘renegade/outsider/performance’ collective Fantastic Nobodies, which operated between 2003 and 2013. He recently created a series of photographic prints for Unit London’s charitable initiative Platform, which were sold online to raise funds for The Campaign Against Hunger. His works are often disgusting, always beguiling, and draw the viewer back in for repeat contemplation. With amped-up performative energy, they combine found object, paint and the body to reveal “unwilling self-saboteur” characters “lost in limbo between the self and the external consumerist world”, according to the gallery. (Emily Gosling)

Jadé Fadojutimi

If the last five years have been dominated by portraiture and figurative painting, 2021 will be characterised by the steady rise of abstraction. Jadé Fadojutimi grapples with her everyday experiences and evolving identity through intensely expressive paintings, which blend riotous colour with intricately observed details. Her canvas becomes a visual map of gesture and movement, where paint and oil pastels collide in ecstatic showers of harmony and disharmony. “One of my studio mates made fun of me; she said watching me paint is like watching me doing aerobics,” the young artist told Philomena Epps in an interview for Elephant in 2017. The push and pull between positive and negative, light and dark, runs throughout her work. Already, the 27-year-old Fadojutimi has exhibited at institutions such as Peer in London, and her work has been acquired by the collections of Tate and Harlem’s Studio Museum. This year she will mount a major solo show at the Hepworth Wakefield, as well as participating in the Liverpool Biennial. (Louise Benson)

Megan Rooney

Canadian poet and artist Megan Rooney often works on uniform canvases, measuring 200 x 150cm, which is the average woman’s wingspan. Her style is abstract and ethereal, formed from multiple layers which are sanded back and then painted over again. She has also taken her sublime aesthetic to the walls of galleries, such as Salzburger Kunstverein in 2020, and Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in 2019, in which her large-scale, site-specific paintings were the backdrop for performers draped in fabric worked into by the artist. In Rooney’s practice, the exhibition text for the latter suggested, we can see “the festering chaos of politics, with its myriad cruelties and the laden violence of our society, so resident in the home, in the female, in the body”. Rooney grew up between South Africa, Brazil and Canada, and has lived in the UK for the last twelve years. She recently joined Thaddaeus Ropac and has her first solo exhibition with the gallery in London this autumn. In her work, “colour becomes a wildfire”, writes curator Anna Lena Seiser, “a living element that morphs and overlaps with other bodies, swallows them up, takes hold of the space and weaves everything together”. (Emily Steer)

- Anya Paintsil, Anya or Anum

Anya Paintsil

It was love at first sight when I saw Anya Paintsil’s work in the flesh during a brief interlude between lockdowns last year. There just aren’t many artists out there who manage to make work that’s as political as it is fun. The unique texture of her work comes from techniques like rug hooking and embroidery, and introduces cotton, real and synthetic hair, hessian and wool to speak materially about her dual Welsh and Ghanaian heritage. Her images deal with the female gaze, personal relationships and collective prejudices, grounded in the specifics of her own experiences (places and people pop up in her titles), but certainly relatable and resonating beyond them. As someone who, like Paintsil, grew up in a mixed race family in a non-urban area in the UK, it’s so refreshing for me—and many others I’m sure will agree—to finally see this perspective out there. The fact Paintsil is already being picked up after graduating last year is a testament to the need there is for such perspectives. Paintsil’s work is on show at the Whitworth, Manchester, when it opens again. She will also have two works on view in Swansea at The Glynn Vivian Art Gallery post-lockdown, and she’s showing in spring at Crafts Council Gallery, London. (Charlotte Jansen)

Cui Jie

As we continue to live through a time that seems more like an elaborate sci-fi dystopia than an actual reality, the paintings of Cui Jie are particularly pertinent. The Shanghai-based artist is influenced by the ideologies of the Bauhaus and Japanese Metabolism, as well as the aesthetics of Chinese propaganda art, to create cityscapes that embrace the conflict inherent in utopian world-building. She warps architectural structures so that they become ephemeral, referencing the airbrushed, graphic art dreamscapes of the 1970s and 80s, while adding her own textured degradation, which reminds us of the transient nature of digital existence and the fallible nature of our societies. Cui Jie is currently exhibiting at the Taipei Biennial, the title of which is You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet, thus serving up an extra layer of existential, celestial crisis. (Holly Black)

- Ayo Akingbade, Dear Babylon still

Ayo Akingbade

Artist, writer and director Ayo Akingbade uses her work to address ideas around “urbanism, power and stance”, and her 2021 looks to be very exciting indeed. Earlier this month her new project, A Glittering City, was set to open at the Whitechapel Gallery, marking the culmination of a six-month collaboration with the gallery’s youth forum, Duchamp & Sons. The works explore local and personal histories, demonstrating the artist’s interest in ideas around identity, belonging, public space and gentrification. Her newly commissioned documentary Fire in My Belly is set on London’s streets, presenting universal ideas of “home, community and crisis”. At the Whitechapel show, this is presented alongside her 2019 work Dear Babylon (2019), a film essay investigating the future of social housing through the viewpoints of three art students. Also this year, Akingbade will be showing her work as part of the Coventry Biennial titled Hyper-Possible. (Emily Gosling)

Salman Toor

The whimsical, sumptuous paintings of Lahore-born Salman Toor are deliciously seductive. The fictional scenes conjured by Toor are immersive snapshots of contemporary life, and you can almost feel the bustling flow of conversation and friendly laughter within them. Their focus is on queer young men at play and at rest, nestled on a sofa or gazing introspectively out of a lonely window. Modern technology, from laptops to smartphones, linger in the background, a reminder of the modern world even amidst the soft brushstrokes of pastel tones that conjure everything from the Baroque to the Impressionists. Toor’s first solo museum show is currently up at the Whitney in New York, cementing his reputation as an artist to watch in 2021. Based in the East Village, he unpicks the intimate interactions of the city, which are so often hidden from view, in paintings that are emotionally charged but never sentimental. (Louise Benson)

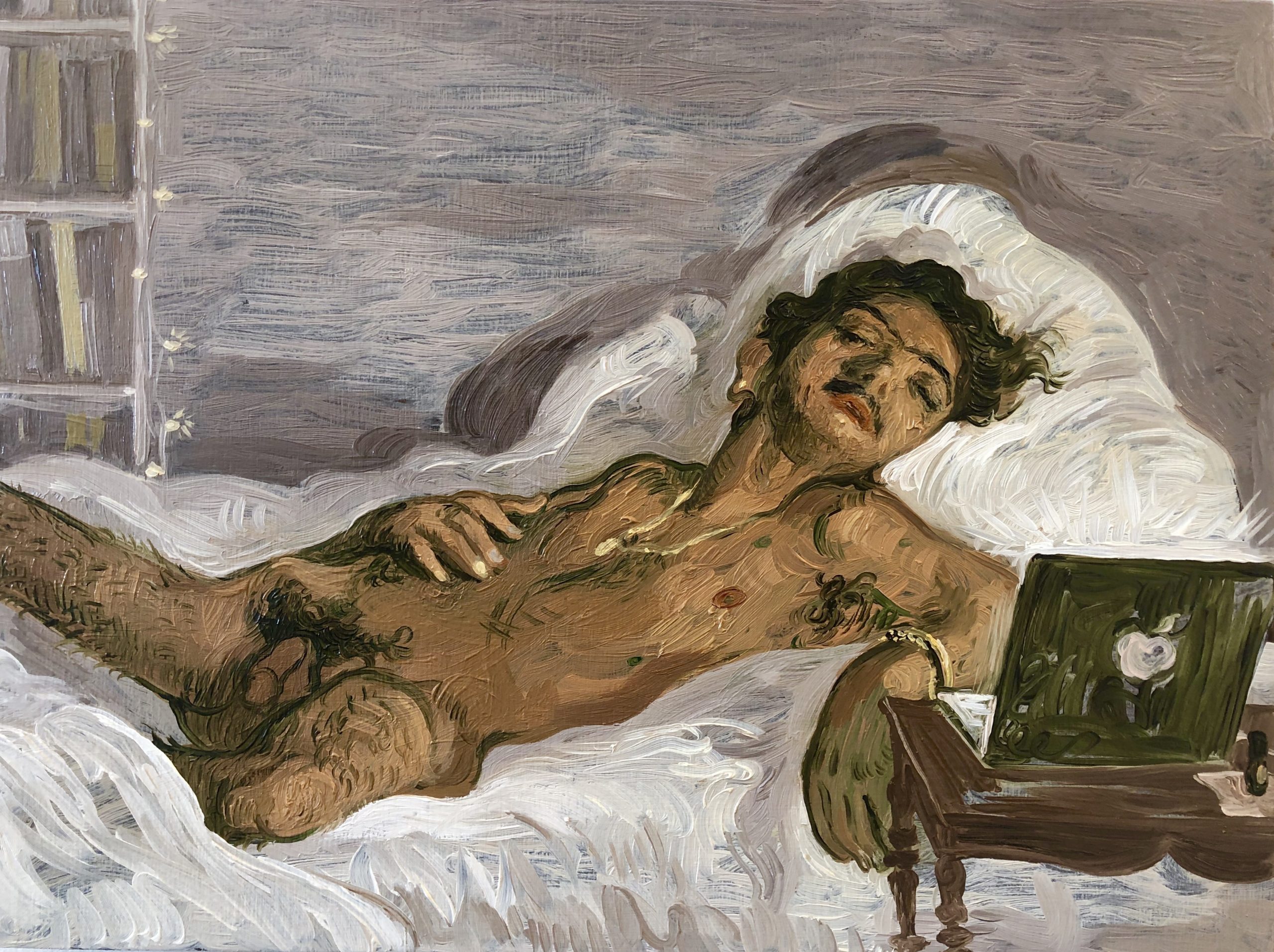

- Doron Langberg, Drawing Mike, 2020. Private collection © Doron Langberg Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Doron Langberg

One of the new cohort of exceptional painters to come out of New York is Doron Langberg, a Yale graduate who works with a narrative, personal figurative language, with free and fluid strokes of oil paint and sometimes pencil. His language is intimate, and his gaze is gently objectifying yet respectful: these are people he knows well, and the closeness of the exchange is palpable. Langberg isn’t afraid to paint a penis in full frontal. Considering we live in a patriarchy, that’s still surprisingly rare. To me, Langberg’s paintings are about the pleasure of looking, at length; they’re about the warmth of real physical human contact, touch and tenderness—things we’ve been sorely missing over the last twelve months. No wonder Victoria Miro announced representation of Langberg last year; expect a London exhibition soon, and much more to come from this talented artist. (Charlotte Jansen)

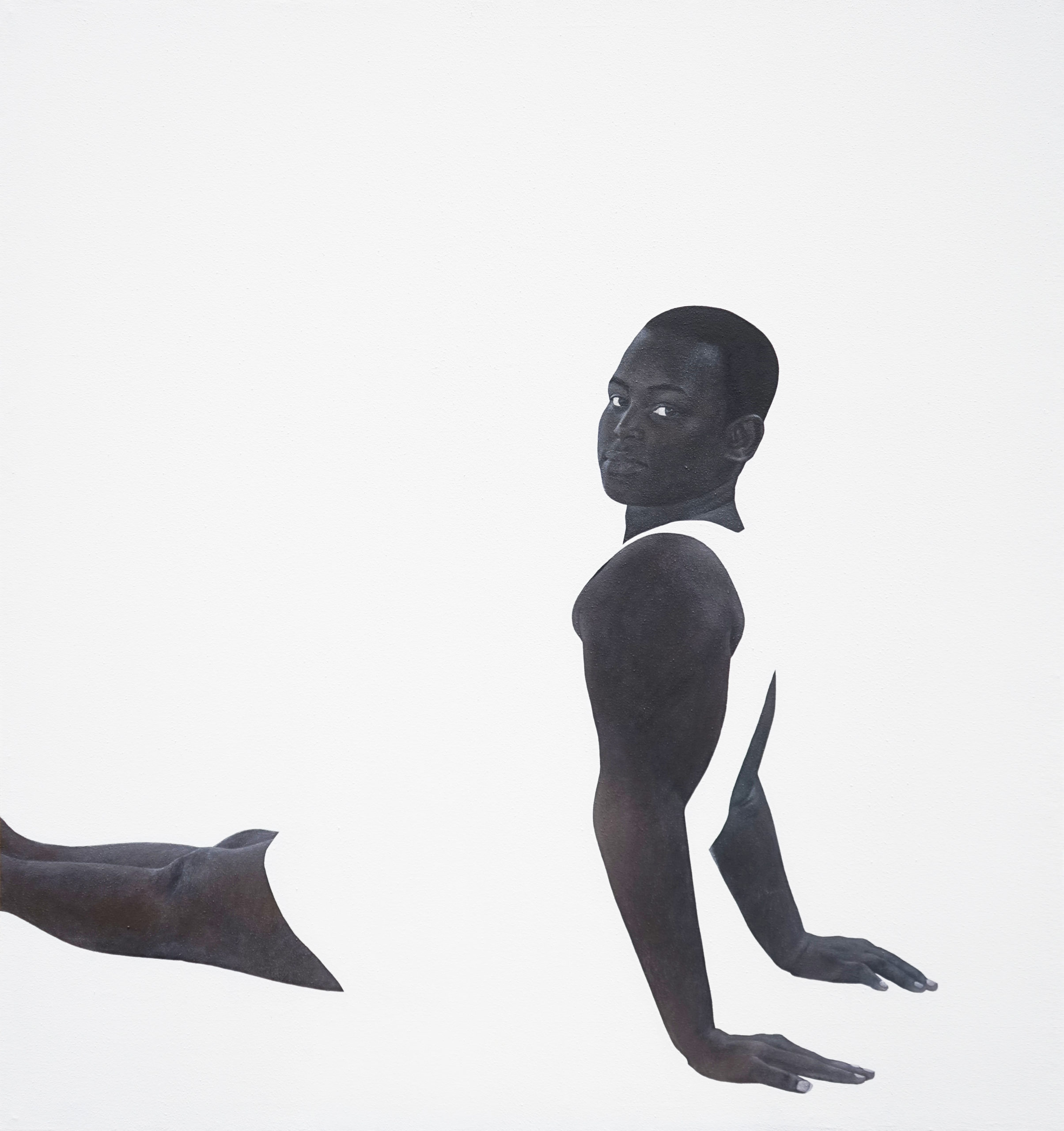

Sungi Mlengeya

At 1-54’s London edition, one of the only places I actually managed to see art in the flesh in 2020, Sungi Mlengeya’s paintings took my breath away. The Tanzanian artist is inspired by the women who surround her in everyday life, often creating group scenes or intimate couplings that craft a distinct balance between negative space and a stylised treatment of the body, which is almost photorealistic in its subtlety. This tension between stunningly rendered detail and flat spatial voids speaks to both detachment and human connection, as all focus is pulled towards the power of physical touch. Astonishingly, Mlengeya is entirely self taught, and only left her job in banking in 2018. Since then she has caused a stir with presentations in London, Cape Town and Johannesburg, as well as a conceptual workshop and exhibition with Afriart Gallery in Kampala. There is surely plenty more to come. (Holly Black)

Lucas Gutierrez

If all its previous iterations are anything to go by, the people behind Berlin’s CTM Festival certainly know a thing or two about commissioning great branding and motion graphics work. This year’s festival is no exception, despite being forced online, as proven by the work of Berlin-based digital artist and industrial designer Lucas Gutierrez. Hailing from Argentina, Gutierrez’s audiovisual practice has seen him work across video art, AV performances, lectures and workshops around the world, with a focus on “the new paradigms of digital culture”, as he puts it. His AV work draws heavily from remix culture, and his realtime performances and lectures merge together influences from contexts that would rarely usually sit together, “from post-work anthropology to the abstract quotes from 3D modelling for industrial design”, he says. Using “the language of colourful, chaotic metaphysics”, his themes often veer towards current social fears and broader dystopian concerns. (Emily Gosling)

- Ad Minoliti, Abstracción Geométrico-Galáctica, 2019

Ad Minoliti

2021 is a big year for Ad Minoliti, who has upcoming shows at Baltic in the UK and MASS MoCA in the US. The Argentinian artist’s utopian work employs vibrant aesthetics, inspired by queer and childhood design, full of colours, shapes and symbols that are often associated with positivity and play. Empathy takes a central role in her work, in which the viewer is invited to engage with geometric shapes with simple hints of facial features. “You can give life to anything by giving it eyes,” she told me late last year. “I find it very interesting to think about how to give life to geometry, and blend the barrier between subjects and objects. A simple shape can trigger compassion.” Minoliti is a trained painter, and has drawn inspiration from Argentina’s history of Geometric Abstraction. While her work celebrates the colourful, inviting nature of childhood design, she explores the pitfalls of the first stages of life too. “Childhood is set up with toys, stories and narratives that force children into a heteronormative life… Being tender, curious, naive or cute is not part of the academic system.” You can read the full interview with Minoliti in our current print magazine, issue 45. (Emily Steer)

Somaya Critchlow

Satire, subversion and sensuality run against each other in the work of British artist Somaya Critchlow, whose figurative paintings of women challenge stereotypes of race and gender. Eroticised to an extreme, her protagonists reveal themselves in semi-nudes and nudes with seductive grace, as if stripping coyly for the ravenous male gaze. Critchlow reclaims the canvas from a heritage of European male painters, from Velazquez to Rubens, introducing elements of kitsch and popular culture to tread the line between seediness and subversion. Since graduating from the Royal Drawing School in London in 2017, she has seen her profile soar with showings at Karma and Jeffrey Deitch in New York, while her first monograph is due out this year. (Louise Benson)

- Kyuri Jeon, Born Unborn, and Born Again, 2020

Kyuri Jeon

I’d not heard of Kyuri Jeon until the recent programme announcement for Give Birth to Me Tomorrow, LUX Scotland’s moving image festival. The festival has been co-curated by artists and writers Tako Taal and Adam Benmakhlouf, who say that the programme lies between moving image, performance documentation, protest documentary and animation, considering strategies for interruption, to undo the formal and psychological trappings of a neo-colonial, white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal cinema system. This is perfectly exemplified in the work of South Korea-born, Philadelphia-based interdisciplinary artist Kyuri Jeon, whose 2019 film Born Unborn Again gave the festival its title this year. Last year, Jeon was one of the eight artists selected by Lino Kino for the Open Video Call annual screening of curated videos by Philadelphia-area artists. I foresee big things for her ahead. (Emily Gosling)

Tiffany Alfonseca

Every so often, you catch sight of something that leaves an imprint: an image or an atmosphere you just can’t quite shake. A painting that stayed with me recently was by Tiffany Alfonseca: purple background, feverishly bright; a seated woman, black skin contrasting with white dress, hot pink sliders, a white dog at her feet. A heady mix of purposeful textures—glitter, acrylic, charcoal, paint markers, oil sticks—and perspectives pack a real punch; the work, Rose Aiello (2020), is just one example of Alfonseca’s ability to arrest. These works are a celebration of shades of Black and Brown in Alfonseca’s community, and more widely of the nuances of the lives of the Black and Afro-Latinx diaspora primarily living in The Bronx where Alfonseca is based. Her next exhibition is happening at Gallery 1957’s new London outpost (due to run to March) and will present a new body of work, Esclavo de la Sociedad (Slave to Society), inspired by Peter Sollett’s film Raising Victor Vargas. (Charlotte Jansen)