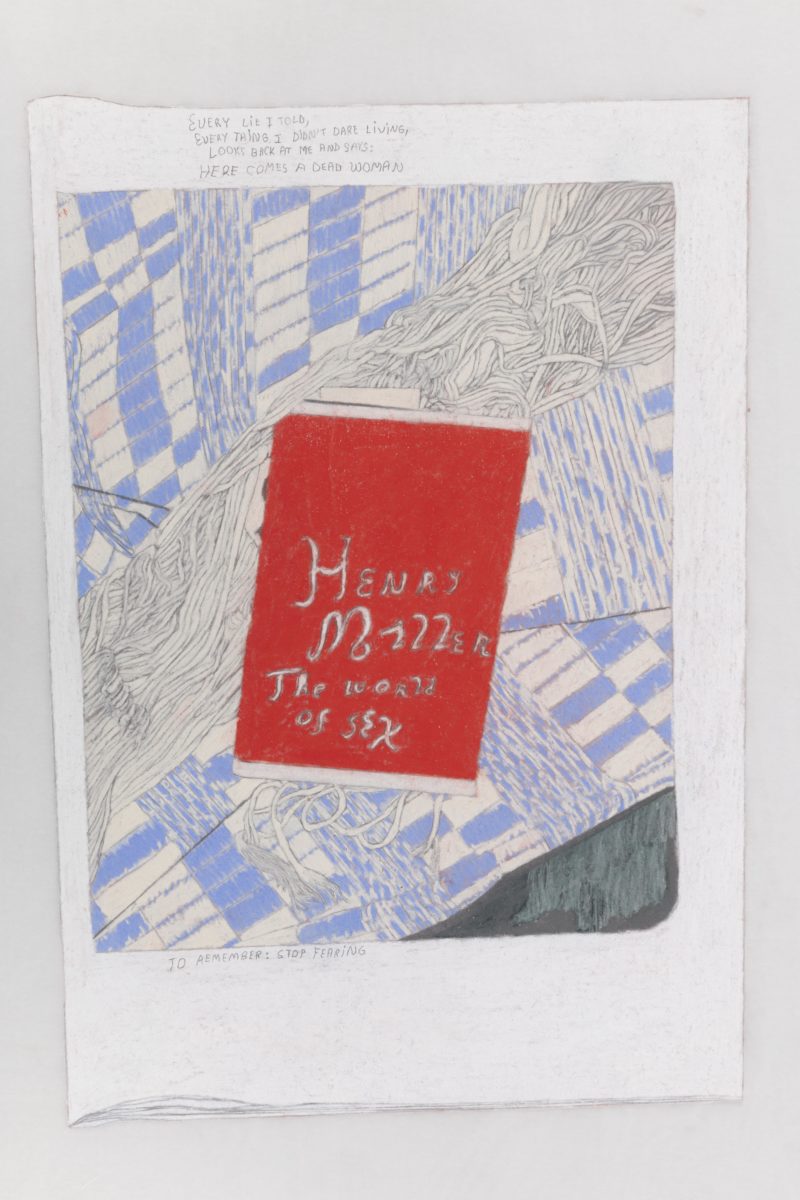

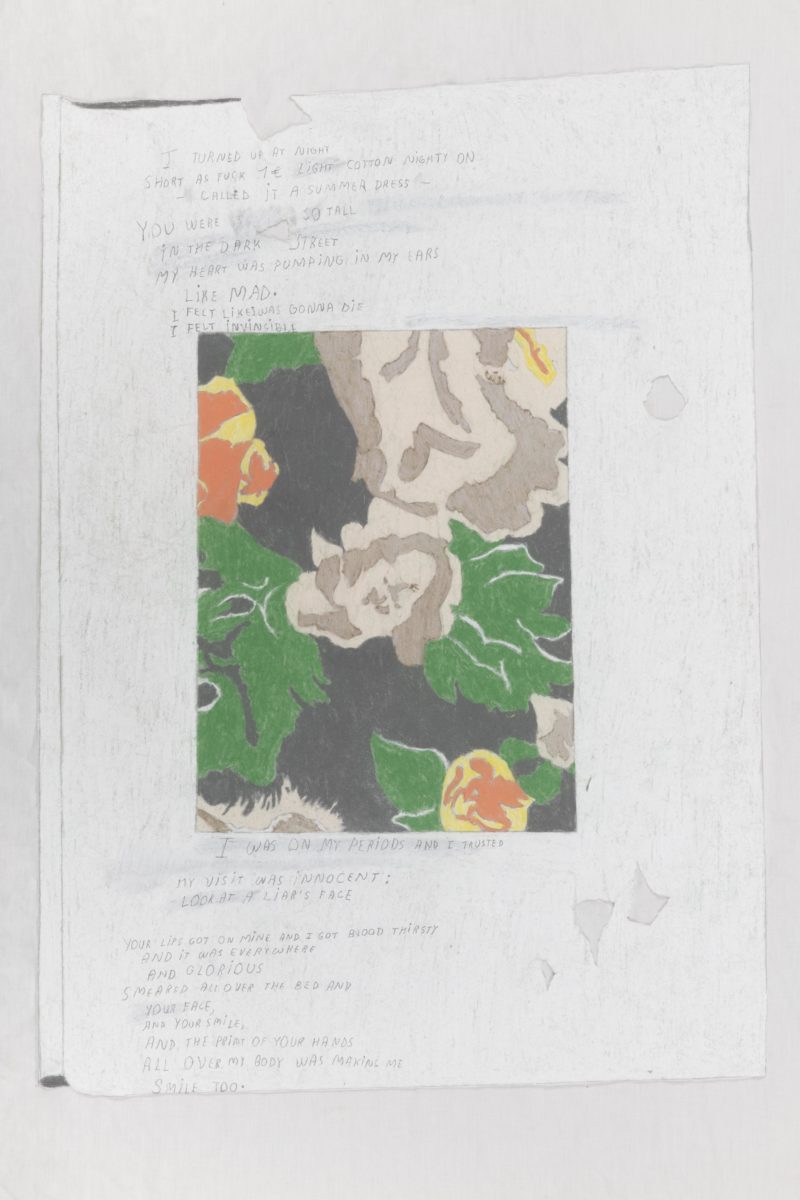

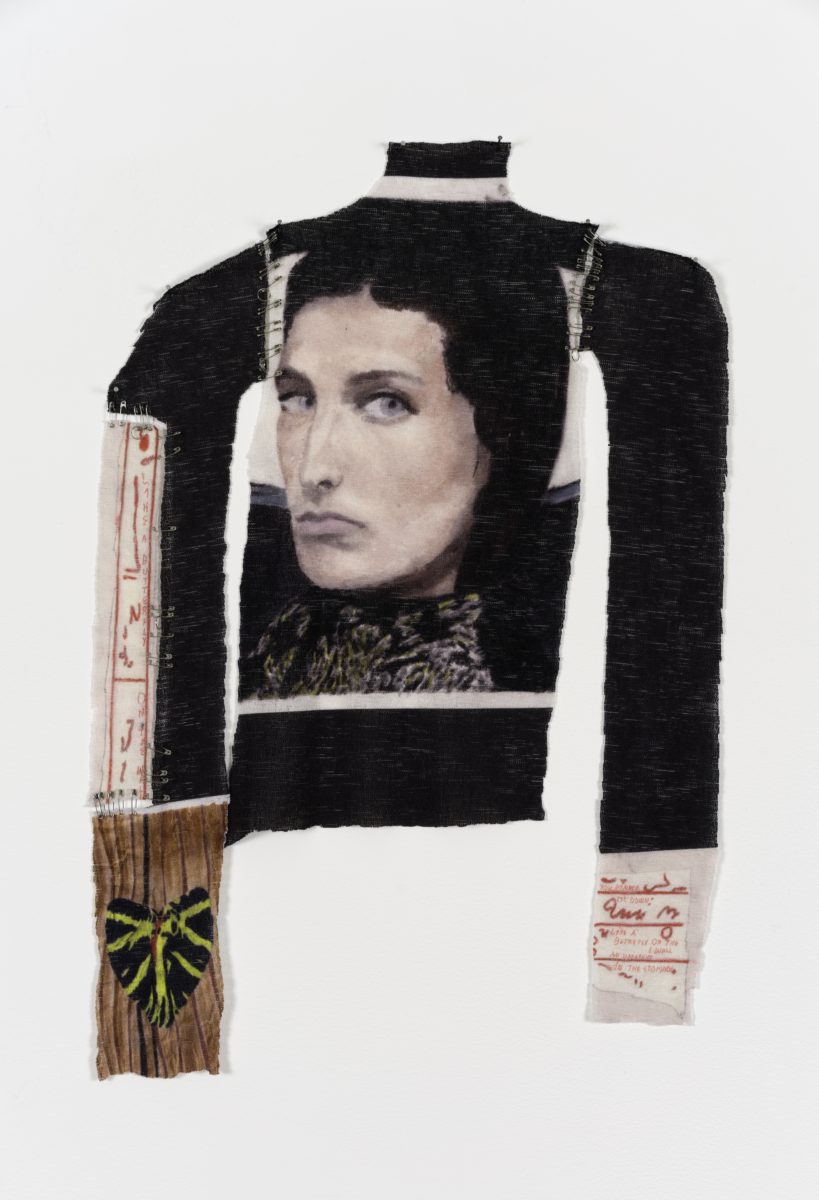

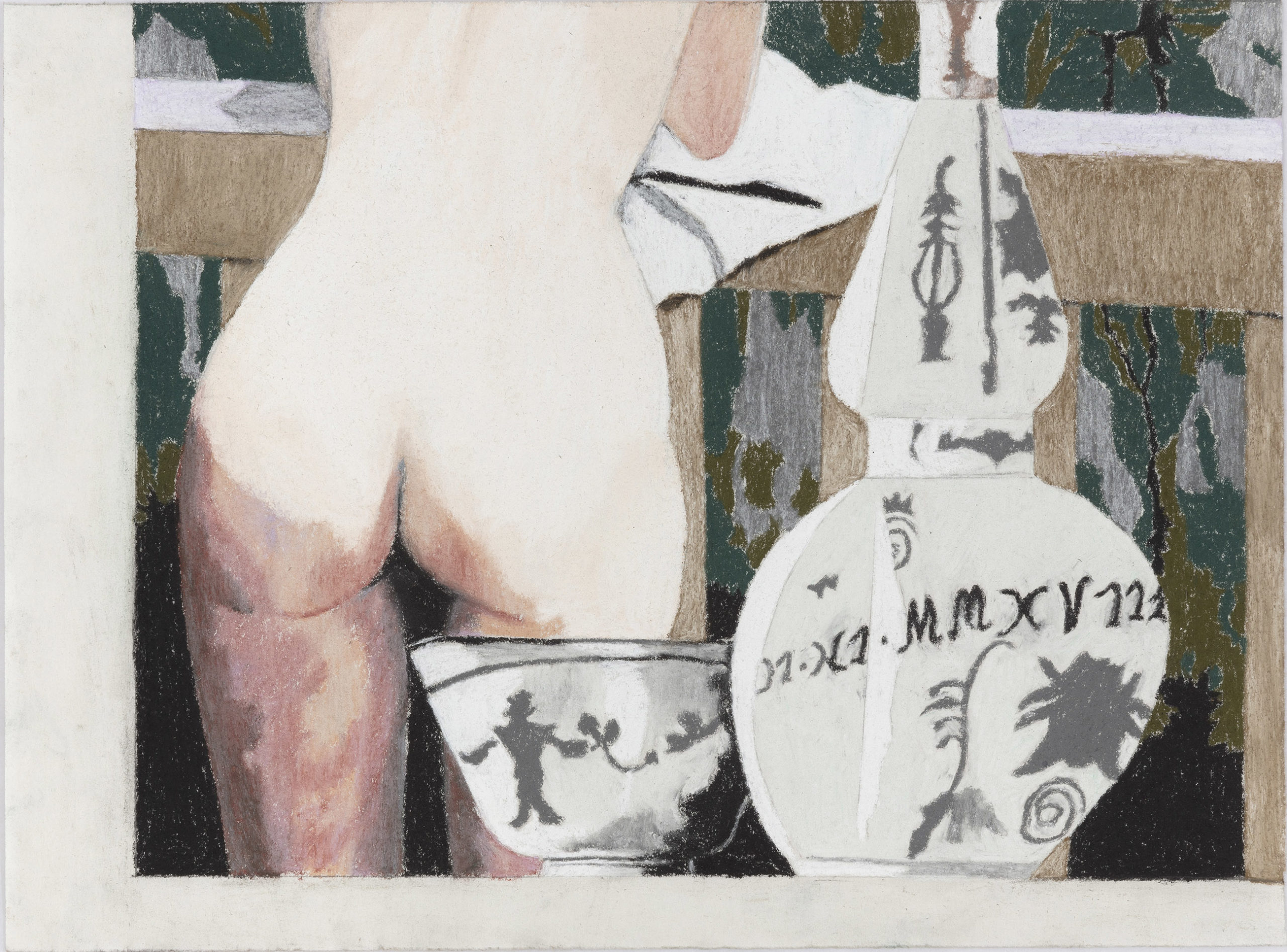

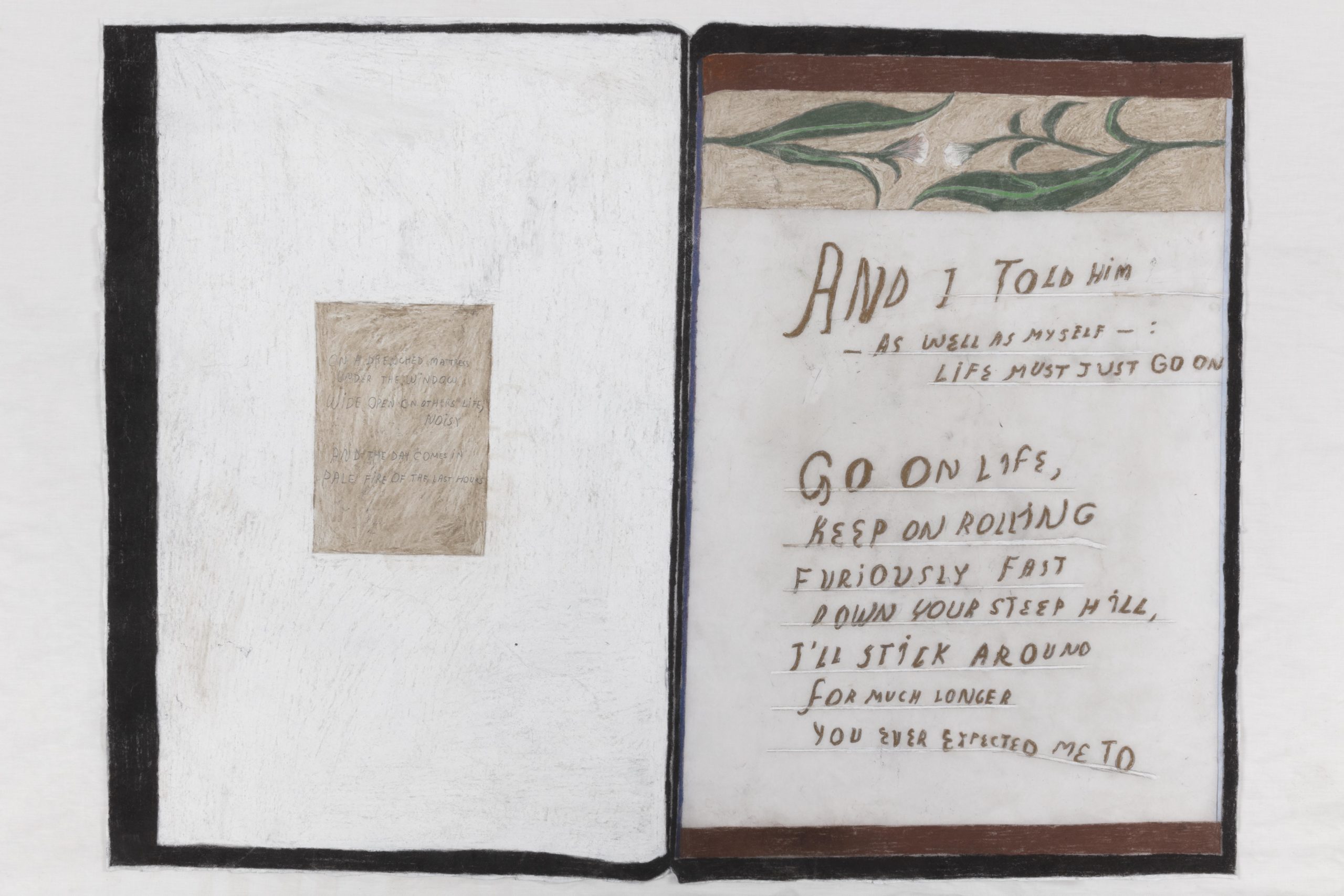

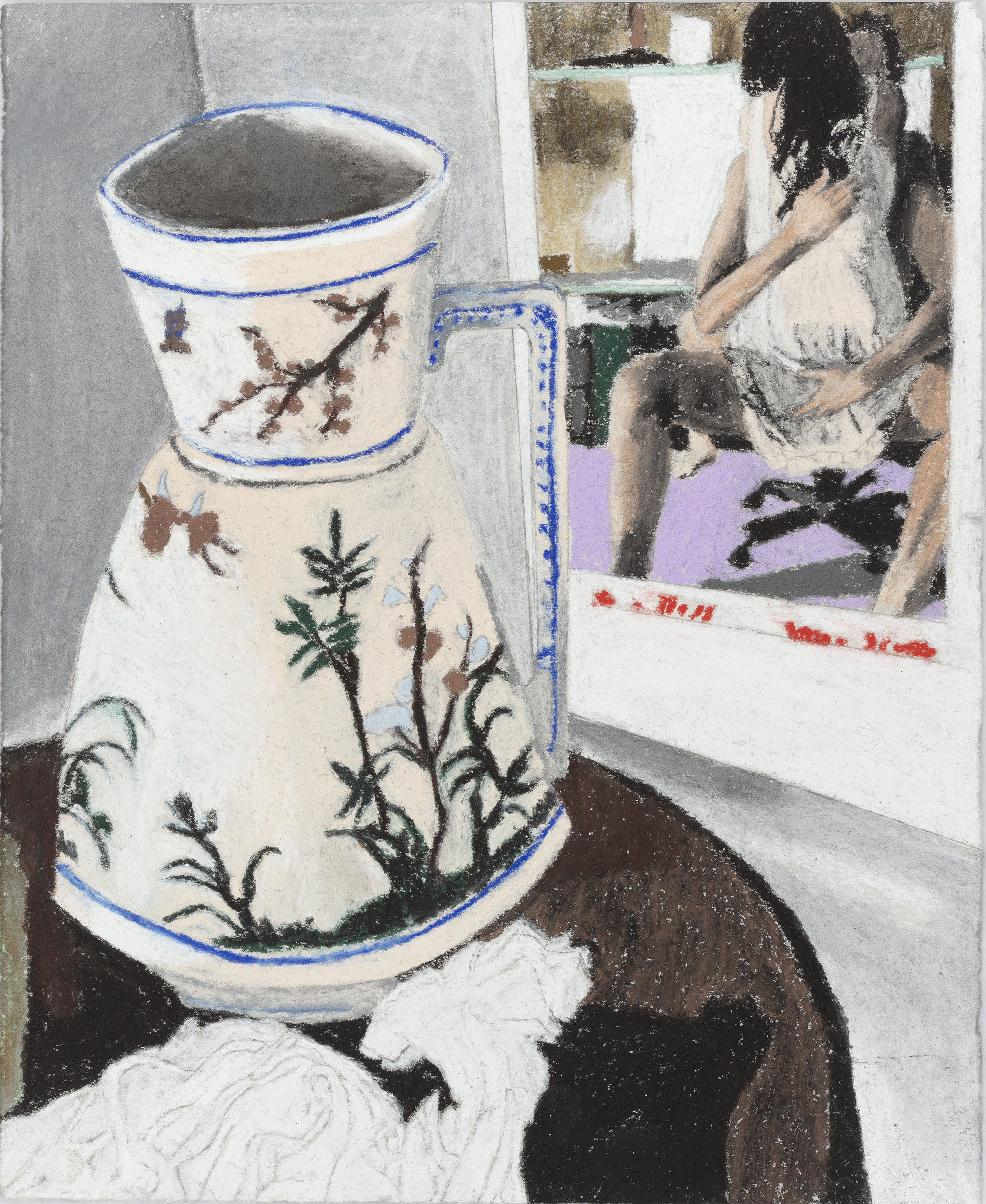

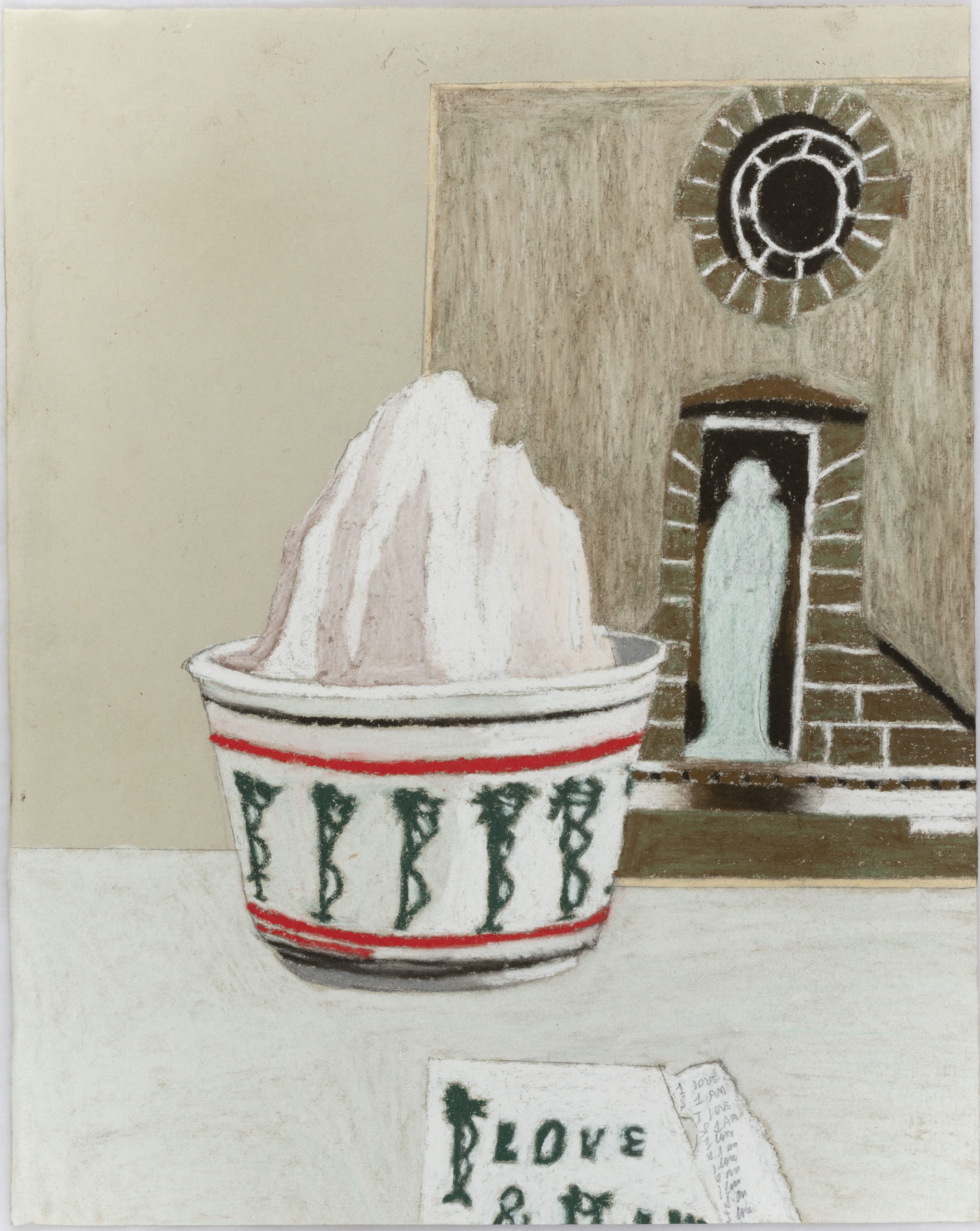

No detail is too small for the roving eye of Marie Jacotey. The French-born artist places drawing at the centre of her practice, using felt tip pens and pastels to sketch scenes from her daily life—from the pattern on a wallpaper to the logo on a friend’s t-shirt. The result is a dizzying array of people and places, as if the imprint of Jacotey’s emotional life has been unpacked upon the page. Her subjects are drawn from a combination of imagery, from her own photographs to classic cinema, cut up and collaged together. It is an approach that mirrors the fragmented nature of her compositions, like an overheard snippet of conversation that cannot quite be put into words upon remembering.

Recently, Jacotey has exhibited at Hannah Barry Gallery, as well as at the Ballon Rouge Collective in Brussels and the Drawing Room in London. There is an intimate quality to her work, as if the presence of Jacotey herself can be felt, furiously sketching alone in her bedroom. At a time of crisis, when many find themselves confined to their home, her focus on the emotional undercurrent of life feels more relevant than ever. For Jacotey, the apparently mundane objects that we surround ourselves with can be the most sacred of all.

Deails from Gloria in excelsis: triptych panels, part of a group show at the Drawing Room Gallery, in London, September 2018. Image Courtesy the Artist.

What appeals to you about crayons, colouring pencils and pastels as your preferred medium of choice? How did you first get into using them, and why have you maintained this as an important part of your practice?

All of these drawing tools (pastel, coloured pencil, felt tip pen) allow for immediacy. They remain at the core of my practice because I am primarily a drawer—it sounds weird to state, but I feel like a painter who would be asked why she is still using painting to make her work. Drawing is my instinctively chosen tool; it has been a very soothing practice to me for as long as I can remember. And it’s super spontaneous, intimate and low-key in its making; in many ways, I find it very comparable to writing, to taking notes. I’ve never felt limited to the paper page. I find drawing an extremely versatile medium that can become anything, really, from a small intimate book to a maximal 3D textile structure, to weird items of clothing or an animation movie.

Your drawings are evocative of everything from childhood sketches to teenage diaries—something that feels more relevant than ever as we collectively find ourselves in our bedrooms in isolation. How do you relate in your work to the emotional dimensions of these domestic spaces, and how has this shifted since the outbreak of Covid-19?

I am fascinated by the depiction of the private—hence a focus on interiors, beds, personal objects, necklaces, candles, flower pots, flowers and framed pictures. But I am also fascinated by flesh bits—a torso, a bare stomach, an arse… All those snapshots are an attempt at capturing what escapes; memories from a moment in time, people long gone, emotions, parts of a life… There is a holy dimension to those possessions, a pulsating mystery surrounding them. The soul that we put into those trinkets oozes through and casts away the thought of death for a moment.

“Drawing is my instinctively chosen tool; it has been a very soothing practice to me for as long as I can remember”

That said, I have not seen a shift in those preferred thematics due to the outbreak of Covid-19 (yet). The only actual shift for now lies in my sanity: I’m a rather a social being. I’m used to being surrounded by friends at work and at home, and I find it to be a good balance to the solitary nature of my work, usually. Being locked in is proving to be a personal challenge in that respect.

The lives of women are often the focus of the narratives that you draw. How important is a feminist perspective to your work, and where do you look to find these often deeply personal stories?

Well, it’s an interesting question because, for a rather long time, I would actually mostly describe men’s lives through the representation of women’s bodies (it would be men speaking in my work). I think that was, among other things, an instinctive way of making my voice as a female author valid (even to my own eyes). My work started to take a different shape as I dropped the fear of appearing to be a certain way: cynical, critical, detached, powerful, in control. I became more involved, using the first person to describe my own personal stories, but never totally autobiographical.

Rather than trying to judge or criticise the way things are, I’m mostly interested in observing and reporting the interactions, events and images of things that have had an emotional impact one me. Those can be cringingly, stereotypically gendered at times because it is a representation of the world as I experience it. And they’re messy because life is messy. I’m not trying to create a message or a reflection of how things should be. In that sense, I consider myself and the way I choose to work to be feminist, but feminism is not the subject matter at the heart of my work.

The smaller details of everyday life are an important theme of your work, from the smell of a cup of coffee to the painful experience of insomnia. Why do you believe that these moments should be recorded, and how do you weave them together into a whole?

Maybe because I don’t believe them to be details; I feel like every bit of everyday life makes for the bigger picture. As I discussed earlier, there is, to my eyes, a tremendous sense of the sacred in those apparently mundane subjects and objects. It infuses the time that I spend depicting those things; curtains, carpets, an Italian coffee machine, the portrait of a friend, the torso of a lover. They are symbols full of emotional stuff, recording the passing, and the beauty and the ugliness, of lives. I guess I’m terrified by the idea of death, and this way of collecting (stories, objects, portraits, landscapes) through drawing brings me a sense of calm and relief.

“There is, to my eyes, a tremendous sense of the sacred in those apparently mundane subjects and objects”

I often work in series, accumulating evidence over what is a passing state of things in my life. In each body of work, pieces interlace together—thanks to my obsessive nature. It will push me to dwell on a certain repeated pattern, for instance, or any random interest of the moment—a colour, clouds or the logotype shape of a brand—over several drawings. It ends up creating a particular atmosphere belonging to that specific period.

Who are some of the artists, writers and graphic novelists who have inspired your work and that you have felt most influenced by?

Luc Tuymans blew my mind in Venice last year. And I’m totally diving into Irvin Yalom’s books at the moment, as well as starting to read the Dragon Ball series. It’s quite broad and eclectic, and I try not to be closed to new stuff, although I just cannot bear horror movies (they actually scare me)! I do have also some very classic loves, like Frida Kahlo, Louise Bourgeois, Henry Miller, Marguerite Duras, Shigeru Ban, early Lucian Freud, Magritte, Henri Darger, Matisse, Annie Albers and John Fante, to only name a few.

But the truth is that I’m mostly looking up to, influenced and admiring of my friends and group of peers. They are the real-deal living artists who make me want to get up and keep working everyday: Kevin Manach, Lola Halifa Legrand, Lucille Ulrich, Paloma Proudfoot, Marina Stanimirovic, Capucine Bonneterre, Alix Marie, Louise Nauton Morgan (STSQ studio), Soft Baroque, Surman & Weston, Stevie Dixx, Thom Trojanowski, Ugo Bienvenu, Hannah Thual, Coline Cuni, Pierrick Mouton, Jamie Shaw, Sophie Demay, Assemble, Nick Ashby, Seb Jefford, Rebecca Ackroyd and so many more. The list could really go on and on and on… Some of them I have collaborated with, lived with, worked side by side with or simply (creepily) stalked on social media. They are writers, graphic designers, painters, sculptors and architects.