During the current Coronavirus crisis, we are publishing one article per week from our latest Spring issue. It is also available to read in full via the Elephant app, or a physical copy can be ordered from our online store.

It’s Thanksgiving in the US and Mickalene Thomas is returning a hire car when I call. She is in the middle of a trip along the coast in Florida, where she is finishing installing her exhibition at the Bass Museum. Mickalene Thomas: Better Nights is set to close in September [note, the museum is not currently open to the public] and it is the second long-running institutional exhibition Thomas has installed in as many months. It is described as an immersive art experience, but Thomas herself calls it a “social experiment”, which incorporates the work of many other artists: the painters Nina Chanel Abney (who shares Thomas’s love of Matisse) and Derrick Adams (who is, like Thomas, a fan of beautiful interior design); photographic artists Paul Mpagi Sepuya and John Edmonds; video maker Ja’Tovia Gary; and Christie Neptune, Devin Morris and Brontez Purnell. The range of work speaks to the breadth of Thomas’s own interests, artistically, politically and aesthetically.

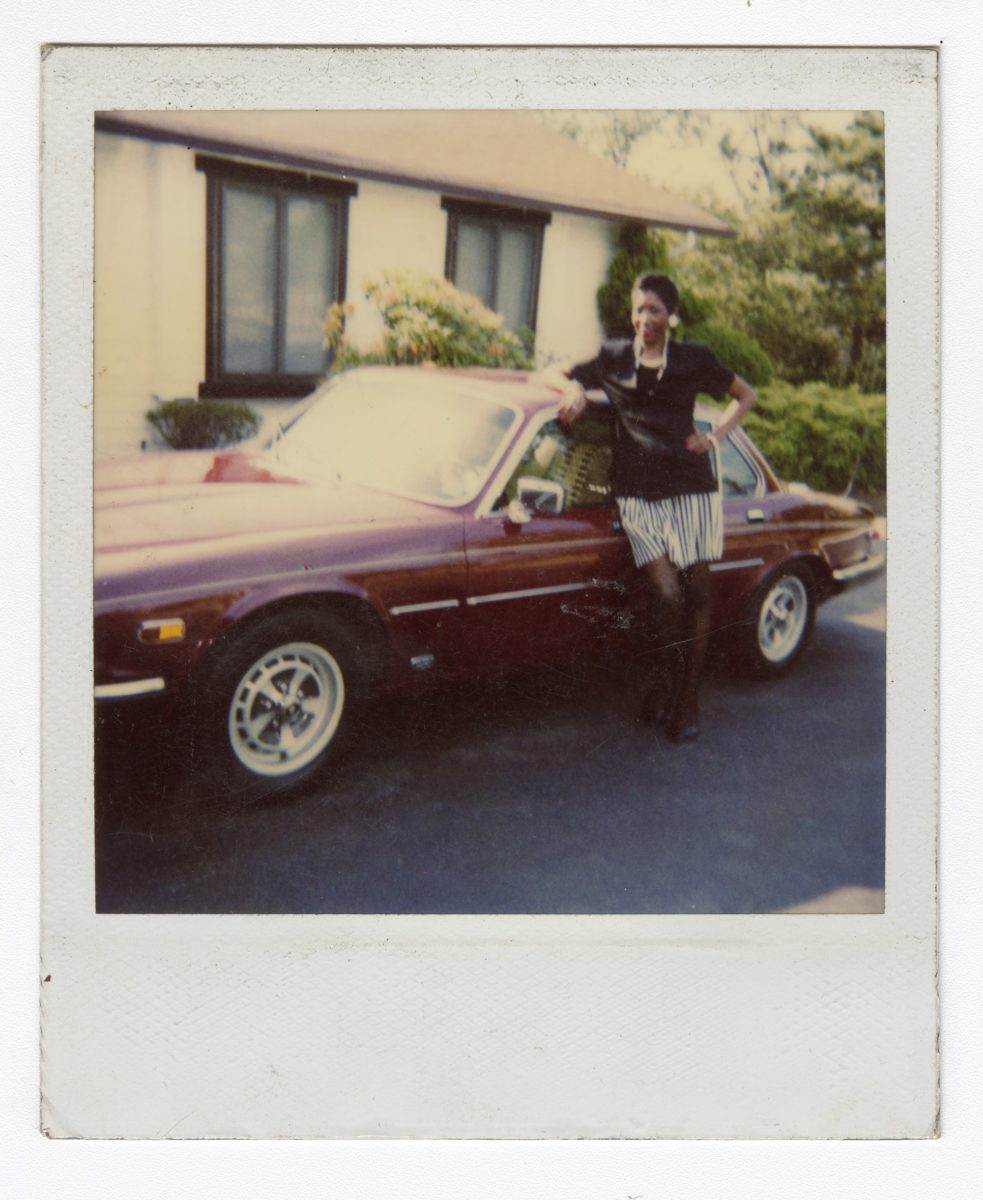

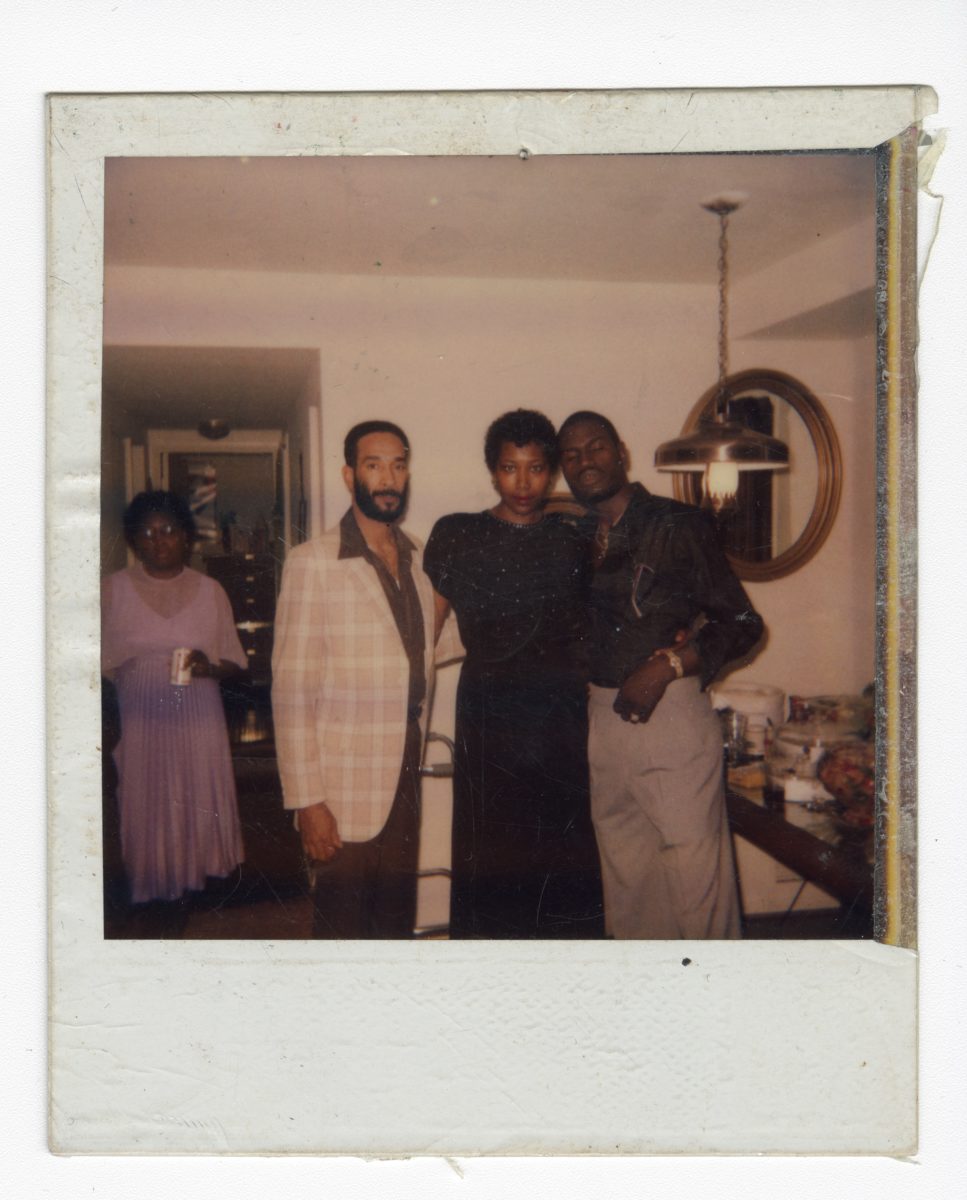

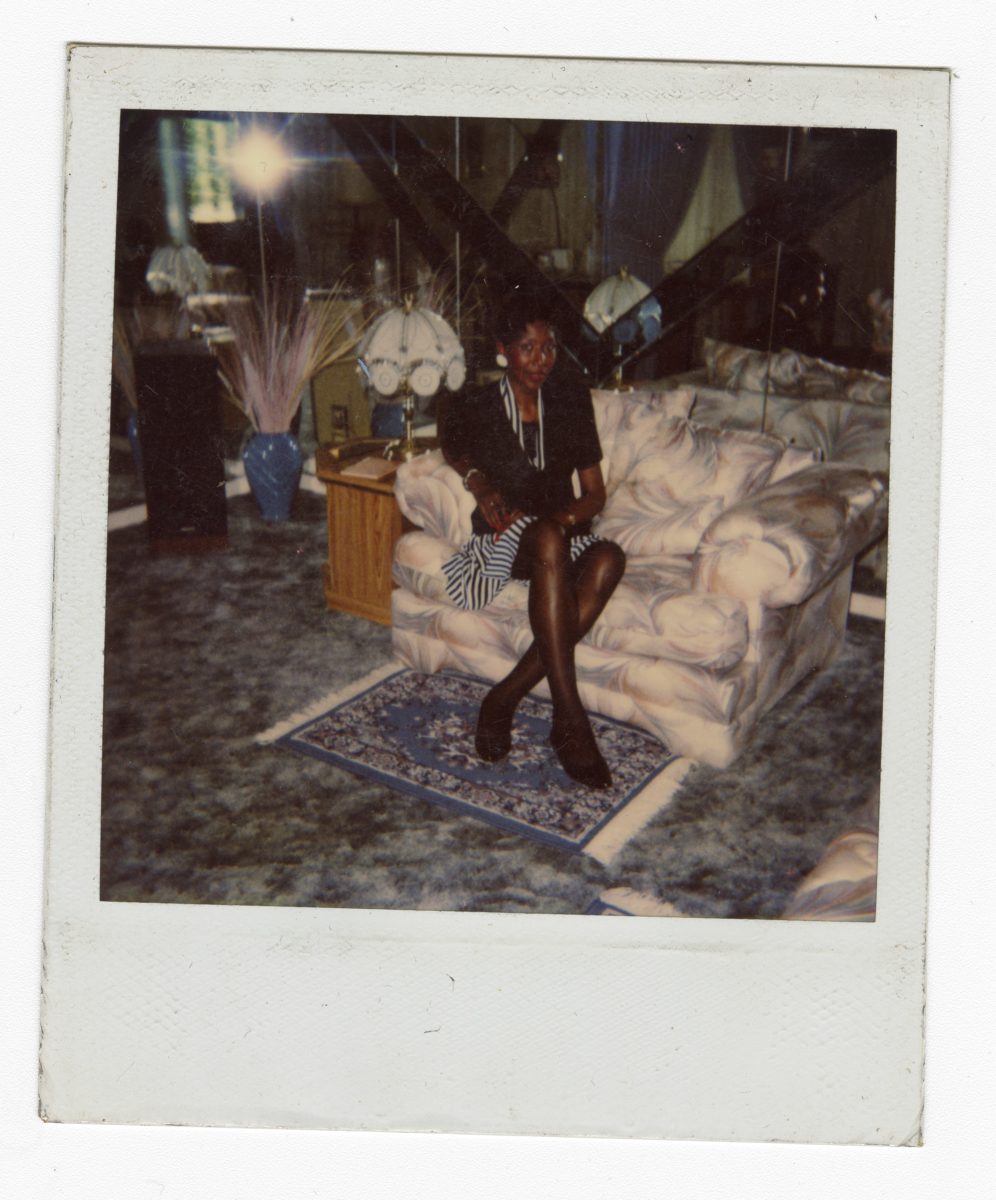

- Mickalene Thomas, Family Photos of Sandra Bush © Mickalene Thomas, Courtesy the artist

Thomas sees this way of approaching exhibitions as “another iteration of curation”, part social-practice, part radical rethinking of the role of the “artist”. “I’m not really interested in doing solo exhibitions anymore—that doesn’t really excite me,” she tells me later on the phone, car now safely parked up. “I want to have a dialogue with other artists, whether they are masters or contemporary.” She rejects the standard practice of showing and selling work every two years. “I just don’t understand that model,” she says. “When I see a show, I want to see the relationships between artists, to make connections on different levels with the work. I’m inspired by other things; so what are those things and why am I not showing them? Why is it just about me?” It might, I interject, be to do with the fact that those models have been based on the mostly male egos of artists and art historians, who wanted to cover their tracks and feign originality for their ideas. “But we know that’s not true—no-one gets to where they are by themselves. It comes from something else, from looking, from digesting—you have to acknowledge that.”

“The seventies were so profound for me, it was a really fierce moment”

This has been the impetus behind all of Thomas’s institutional exhibitions in the last year: building a community that can bring joy, but that also addresses what Thomas sees as a real concern in the art world. Since her breakthrough exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in 2016, Thomas, aged forty-eight, is now one of the most sought-after artists in the US, both in terms of the market (her photo-collage portraits regularly fetch upwards of $20,000 at auction) and in terms of institutions inviting her to stage headline shows. “The opportunities have allowed me to make bodies of work that I’ve wanted to do for a long time, but also to create platforms for other artists, specifically emerging artists, and to provide opportunities for them too.”

“There are a lot of artists who aren’t getting the visibility they need, so when I have the chance to exhibit in particular institutions it’s part of my responsibility to provide some of that agency and to hold the museum a little more accountable,” she adds. “No-one wants to be at the top by themselves; at least, I don’t! I want everyone to have a seat at the table.”

If the demand for visibility has been at the centre of Thomas’s work since the start, she’s now taking it to a whole new level. Where she used to paint and photograph mostly black, female figures (her late mother; lovers; her chosen family) back into the world with what bell hooks might have called an “oppositional gaze”, Thomas is now insisting on seeing others as they want to be seen, by directly introducing diverse voices. “I want the room to be peppered with diversity and many types of people, people of colour, different genders… that’s what the room should be like. The art world needs to be the leader in a changing world. Oftentimes artists who are in the most vulnerable places are the ones who step up and take the risks, to ignite those conversations, to see if it generates new conversations and discourses that move the needle and force people to start thinking of new ways to create exhibitions.”

The process in itself is revealing: while there is a huge demand for diversifying, the figures often reveal that little progress has been made. Commercial gallery representation and museum acquisitions are still vastly tipped in favour of white, Western men. Clearly, there’s a degree of lip service going on. Thomas wonders whether her ambitious new way of creating exhibitions will have an impact on which institutions invite her in the future. For now, despite some bumps in the road, she is enjoying being able to impose her demands. Even as the works are going up at the Bass, “I feel like we’re still struggling to get an understanding of what this mission is. When I said I wanted to involve locals, it was kind of dismissed,” she admits. At Baltimore Museum of Art, she opened A Moment’s Pleasure in November (the show, temporarily closed until at least the end of April 2020, is set to run until May 2021). “Their involvement with what I’m doing, and my vision, has so surpassed my expectations. They have held themselves accountable in such an incredible way. They decided to take responsibility, to really engage their departments and their community.”

- Mickalene Thomas, Family Photos of Sandra Bush © Mickalene Thomas, Courtesy the artist

Thomas is aware that what she’s doing disrupts the rubric. “It’s not a political move, it’s more of a conscientious way of being an advocate for others, and it’s about mentorship—that’s one of my missions and visions as an artist. As I grow as an artist, I want to be able to foster and bring others up with me. I think it’s because I didn’t have that support—that’s why I want to create this. The artists I looked at didn’t have those resources, they were very limited, they couldn’t provide that support even if they wanted to. They’ve opened the door and laid the groundwork for artists like me to do this now.” Being in one of Thomas’s exhibitions isn’t just about art “hanging on the walls”, it’s an invitation to be “part of a family”.

An early encounter with a work by Carrie Mae Weems in Portland was a complete revelation for Thomas—the decisive moment she became an artist. “It transcended me in such a big way,” she recalls. She also mentions Faith Ringgold as someone who set a precedent for her path. “But I didn’t have access to them then—it’s not like I could go up to Faith and say, ‘Hey, how did you make this work and how do you navigate the art world?’”

Thomas’s partner, the art consultant and collector Racquel Chevremont, has played a major role in her work, both as a muse and a collaborator. It was Chevremont who got Thomas’s 2010 painting Le Dejeuner Sur l’Herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires—a riposte to Manet’s Impressionist work from 1862—on the hit American TV show Empire. It’s perhaps no surprise that since the pair became a couple seven years ago, Thomas has been on the rise. Chevremont played a fundamental role in Mickalene Thomas: Femmes Noires, a show that travelled from AGO Toronto to the CAC New Orleans. Le Dejeuner Sur l’Herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires was a centrepiece of the show, alongside works featuring characters like Shug Avery from The Color Purple and Dynasty star, Diahann Carroll.

This kind of representation matters. At her New Orleans opening, Thomas had an experience she says she won’t forget. “There was a woman there who came up to me and just started crying. All she could do was say, ‘Thank you, thank you for this.’ She was so full of joy that this work was there for her. It is incredible for me, when people feel that. That’s real. That’s what it’s really about—that’s why I love doing what I do.” Emotion clearly present in her voice, she continues, “You can feel it when people see themselves; that’s the power of art—that’s the power of representation. It’s transformative in a big way.”

- Mickalene Thomas, Family Photos of Sandra Bush © Mickalene Thomas, Courtesy the artist

Educated at Pratt and then Yale, Thomas is used to institutions, but she emerged into the art world ignorant about the business side of art. Perhaps it’s Chevremont’s insight, but she now seems savvy about the pitfalls of the art market, and that knowledge is something she wants to share. “Artists are often getting into very tricky situations because they don’t understand the business of the art world, it isn’t taught in art schools, and galleries don’t educate their artists, so you have to learn from your own errors,” she explains. “On top of creativity, it’s a huge part of an artist’s work, but no-one talks about it.” With Chevremont, she’s also founded The Josie Club, a support network for queer women artists of colour, to help fundraise, sponsor and support their artworks. Is this social practice something we can expect from Thomas in the future? “Oh yes, we’re just getting started!”

“I think it is very exciting for black and brown artists right now. But art is fickle and unpredictable”

It all makes perfect sense looking at Thomas’s works: whether it’s in paintings or installations, she often creates a homely atmosphere, comforting and comfortable. In their details they often recall her own home, growing up—her installation at the Bass references happenings at her mother’s in the 1970s and 1980s. The family atmosphere seems to be a natural extension that has evolved into her new way of working. “I think for me, it’s about creating that kind of intimacy with people, because oftentimes people have to create chosen families, right? That’s something that has been known in the queer community for many centuries.”

The 1970s is a decade that Thomas constantly comes back to in her art: the fashion, the decor, the vibe. Why does she think the seventies continue to be mythologized in visual culture, even by people who didn’t live through the period? “I guess for me it’s mostly about the 1970s Black Radical Aesthetic, which created a lot of joy,” Thomas reflects. “Everything that was happening at that time—from the ongoing Civil Rights Movement to the Black Panthers, to Black Is Beautiful—it was about self-identifying and people taking full agency of themselves, creating these collectives and uprisings. And it was a time of political activism, whether vocalizing on the streets or through entertainment, things were radicalized in a huge way. The seventies were so profound for me, it was a really fierce moment.”

Does it compare to the presence and power of black artists in America at the moment? “I think it is very exciting for black and brown artists right now. But art is fickle and unpredictable, it’s like a tidal wave; first it was Latin American, then Chinese, then Middle-Eastern, now it’s black American—we don’t know how long that wave will stay up high, but the surfers are riding that wave really well right now,” Thomas responds. “I’m excited about it and I’m enjoying some of the rewards, I know I’m benefitting, and some of these shows have to do with it currently, but we have to ensure there’s no backlash and that we don’t look back and see this moment as only a politically correct movement. We’ll all still be here making art, whether it’s a good ten-year period or not—it’s about what’s going to happen after that moment is gone.” If it’s left up to Thomas, there’s no doubt their legacy will endure.

The Elephant Spring issue is available to read in full via the Elephant app, or a physical copy can be ordered directly from our online store.

READ NOW