Abel Rodríguez saw the sea for the first time this year. He was in Newcastle for the opening of his first international solo show at BALTIC Gateshead, which opened on 13 March and coincides with the inclusion of two more of his works in the show Among the Trees (4 March – 17 May) at the Hayward Gallery in London. A pretty significant event for any artist, but Rodríguez is fairly adamant that isn’t a category into which he falls. He welcomes the art world as it comes to him, enjoys the slightly easier life that interest in his work has given him, and was apparently delighted by the sea, but fundamentally he remains a man of knowledge to be shared for the good of the forest and of people.

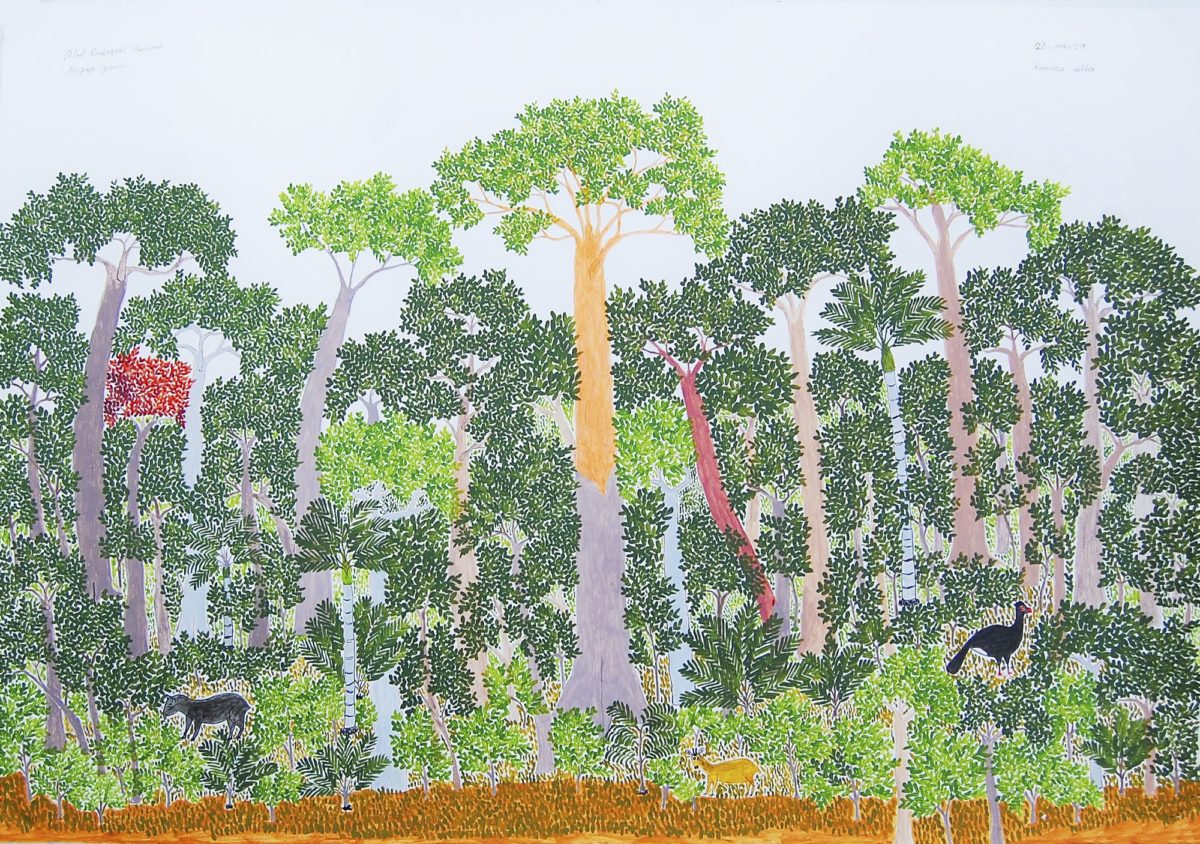

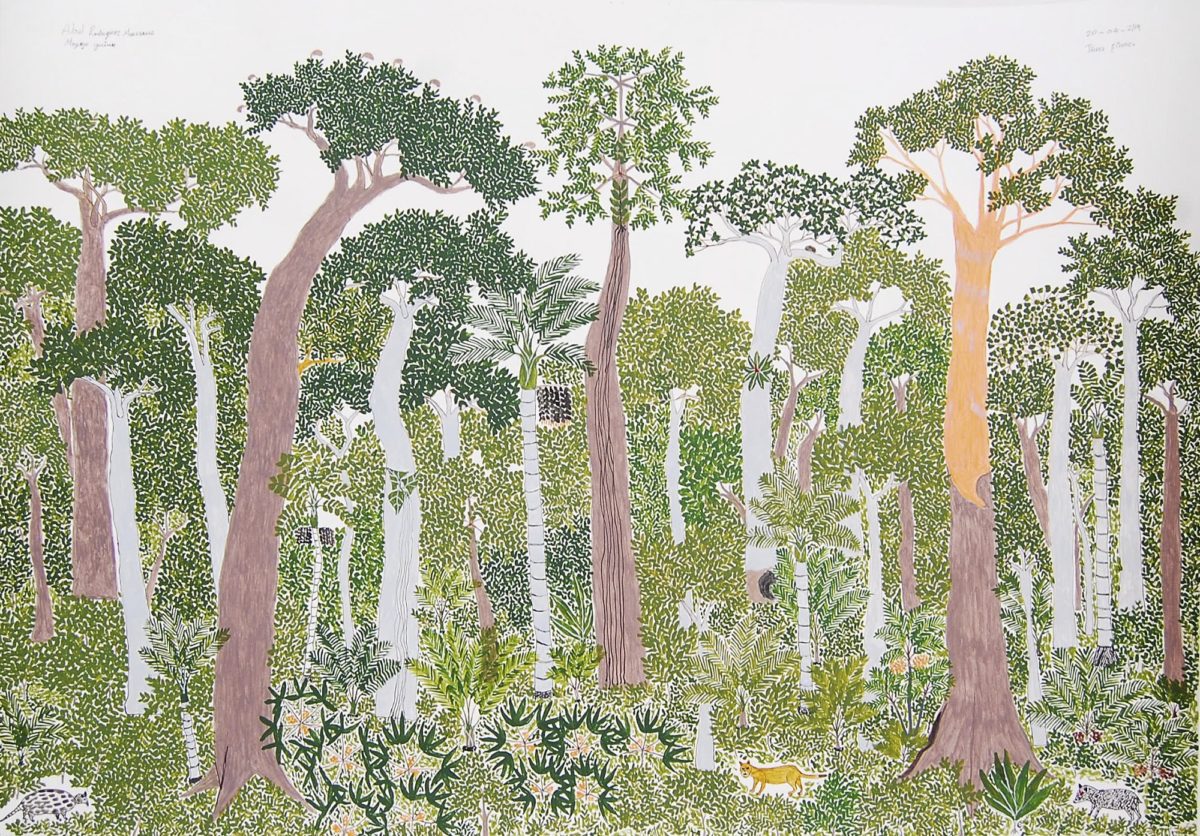

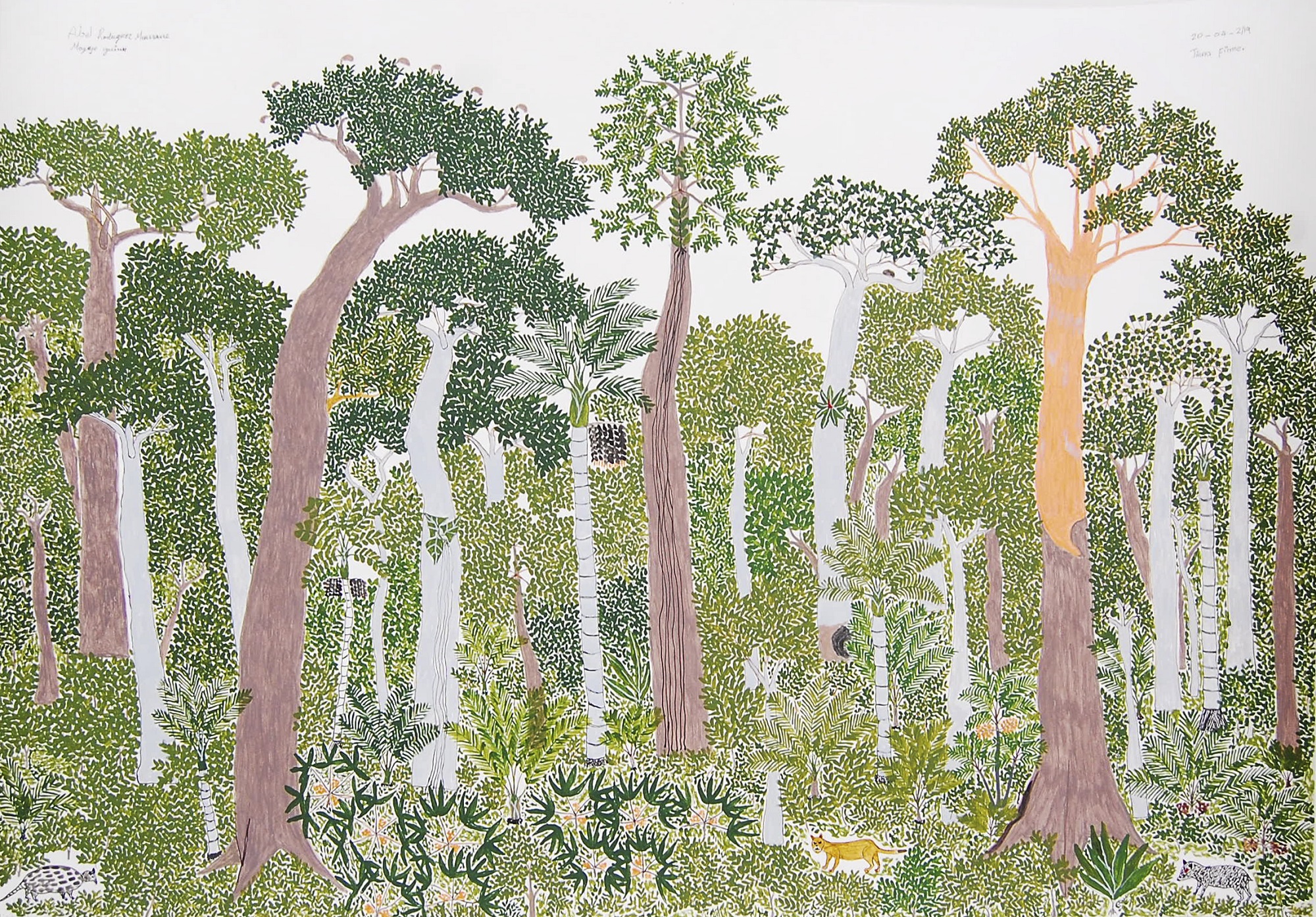

Abel Rodríguez, Tierra Firme III, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Instituto de VisiónBorn Mogaje Guihu, as part of the Muinane Hawk Clan who live on the Cahuinari River in the Columbian part of the Amazon, Rodríguez grew up training to be a sabedor (or shaman). His purpose in life was to share the knowledge gathered painstakingly over years—the knowledge of plants. Rodríguez knows every plant of the region he grew up in, he knows their life and death

Abel Rodríguez, Tierra Firme III, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Instituto de VisiónBorn Mogaje Guihu, as part of the Muinane Hawk Clan who live on the Cahuinari River in the Columbian part of the Amazon, Rodríguez grew up training to be a sabedor (or shaman). His purpose in life was to share the knowledge gathered painstakingly over years—the knowledge of plants. Rodríguez knows every plant of the region he grew up in, he knows their life and death

cycles, knows the animals and insects they attract, and those they repel, knows how they rot and how they seed, what they cure and what they kill. One kind of rubber milk can be used to create “nappies” for babies, and also to facilitate abortions. This is his practice, craft and work: remembering, knowing, and showing.

“This is his practice, craft and work: remembering, knowing, and showing”

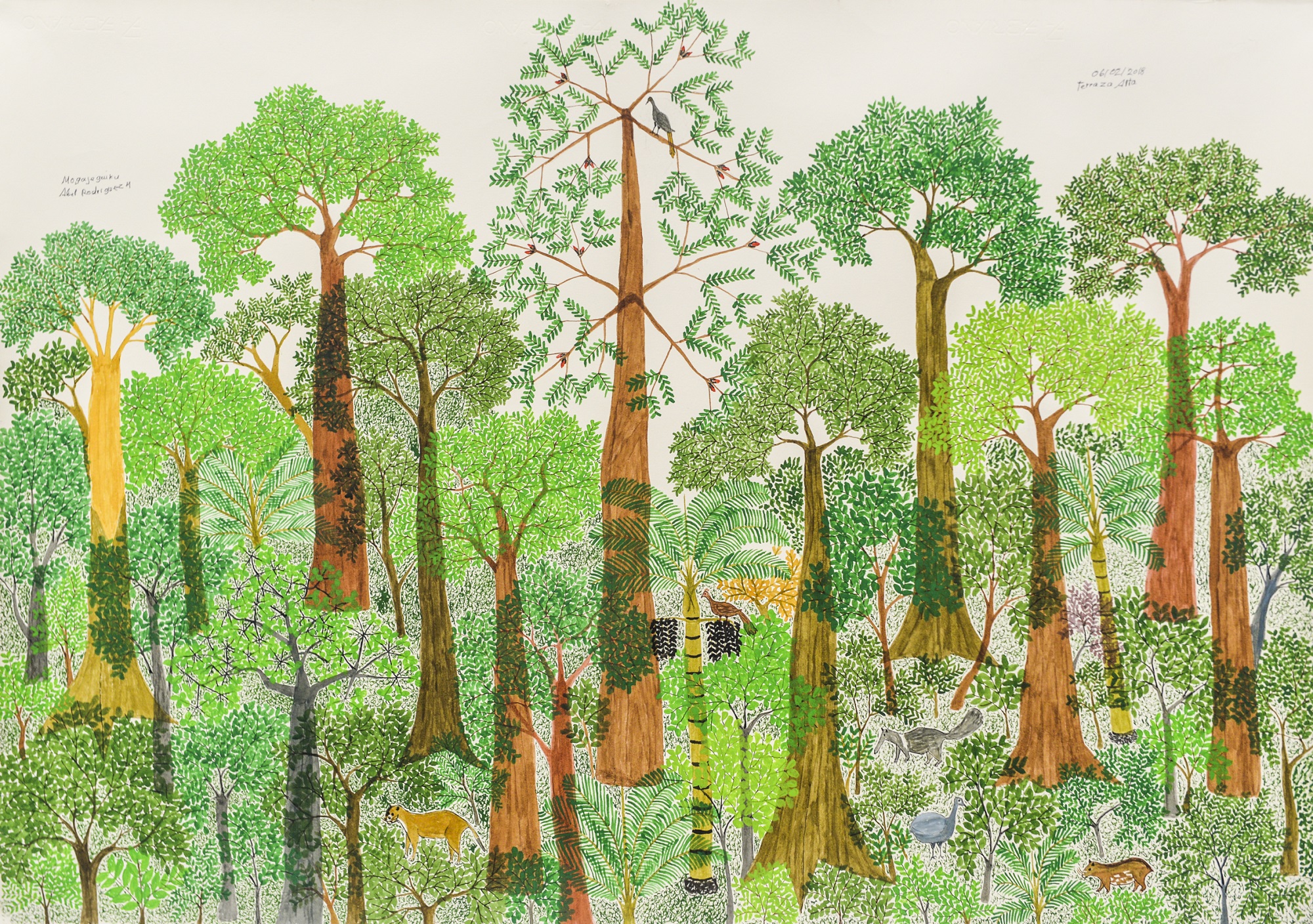

Hired by Tropenbos, a Dutch NGO, to share his knowledge of the plant life of his native region, he was asked to turn to image-making as a way of teaching and sharing his ancestral knowledge, passed down to him by his uncle. Beginning in felt tip pen, before he gained access to Chinese inks, Rodríguez created botanical illustrations of the plants, environments, habits and creatures of the rainforest in what he considers their most fundamental and recognisable form. He draws simply because he enjoys it, and draws things “the way they are, so they are beautiful.” Rodríguez believes in an intense subjectivity, every person according to learning and training having a completely alien set of eyes and values. He does not give his drawings the same “luxury” value others perceive in them, nor are the things he looks for in plants the same as others would notice.

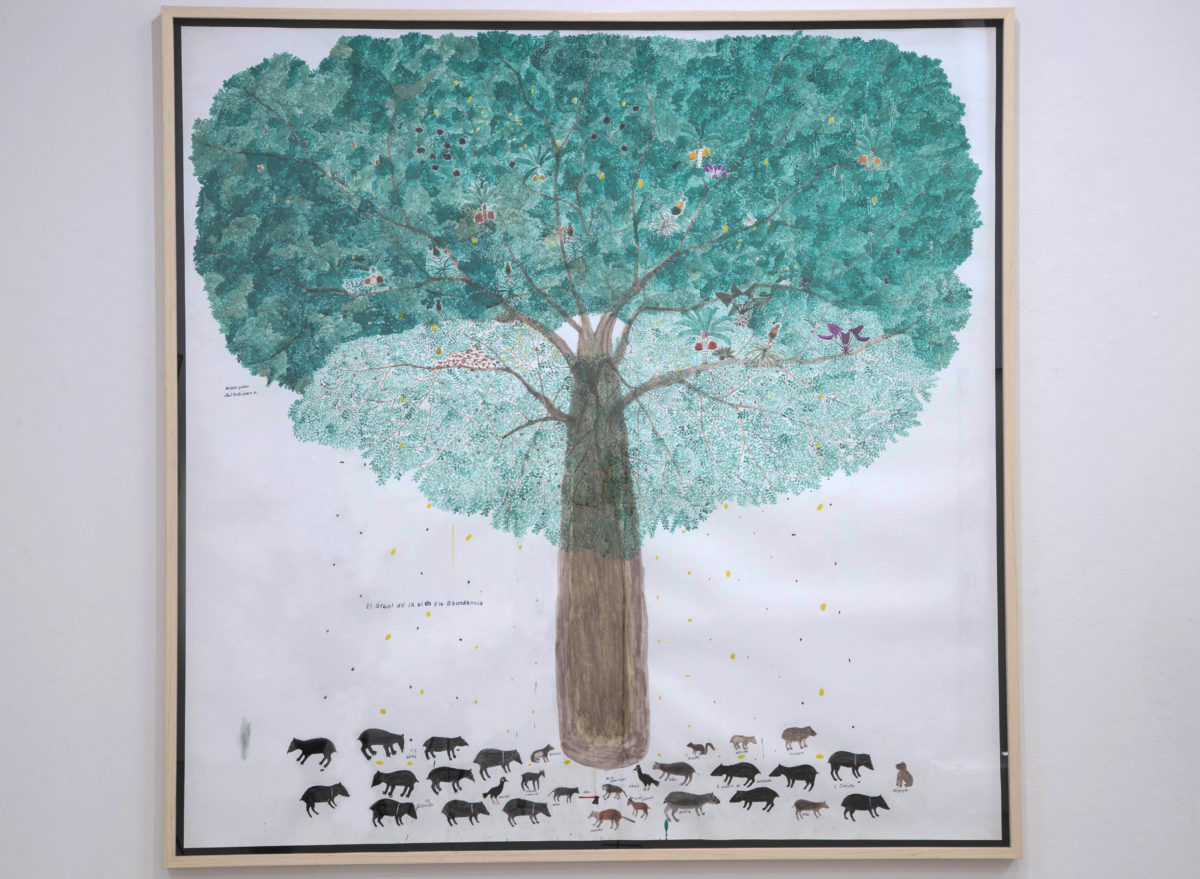

That being said, for those raised in a world that trains the eye to seek out luxury, the drawings have the ineffable (and therefore luxurious) quality that marks them out as “art”. To use the word lush seems like a cliché in this context, but these images are so densely layered they they feel almost enlivening. Animals and fruits are woven in according to likely habitat, and often labelled accordingly in both Spanish and Rodríguez’ indigenous language. He writes everything bilingually and always signs both his names, a quiet insistence on his truth, and on preservation.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Rodríguez is sensitive to shades of green, but when a tree is purple he paints it purple, because in a sea of green, purple is a notable quality to express. Expression is key to how the drawings function in more realms than just the aesthetic. Rodríguez started drawing to help outsiders see and understand the forest, and he achieves that by using the expressive qualities of ink and paper. His marks and strokes don’t have the same optical precision as traditional European botanical drawing, but they have something almost more helpful—they convey more recognisable qualities than simple form. The droop of a line suggests heavy leaves on a stem, and the tiny spiky flicks of paint are more evocative of massed leaves clumping distinctively on sky-reaching branches. His drawings aren’t exact but they are accurate, and they are accurate through expressive handling of materials, and an instinctive understanding of aesthetic weight.

For drawings of single plants he scales up the same techniques, emphasizing the same distinctive qualities of each plant, listing their uses and adding small visual addendums detailing fruit, seed pods, and the birds and animals which eat, use or nest in them. From these individual drawings it is possible to start to pick out species in his bigger scenes, just based on the unique way he draws each one. After some minutes of immersive study, it’s almost possible to understand which drawn plants correlate to the aerial shots of the rainforest in the accompanying film by Fernando Arias, which documents Rodríguez’ life and understanding. His drawings operate effectively as tools for the sharing of knowledge, which is the role in life to which he was raised—before encroaching violence and development forcibly relocated him to Bogata.

Rodríguez completes these drawings in the city, working not from life but from an encyclopedic knowledge and awareness of the forest, its life and its cycles. For the Muinane every plant is sacred, especially the yucca, coca and tobacco, which all have important roles in regulating mind, body and spirit in relation to the all-encompassing Tree of Life. The Tree regulates and sustains the ecological and social relations of the forest, and the world. His drawings of his indigenous way of life, its dynamic cycles responding to the forest and the water, reflect this saturated worldview.

“For Rodríguez, the path to becoming el nombrador de plantas was a spiritual one, involving long hours at the feet of elders”

For Rodríguez, the path to becoming el nombrador de plantas was a spiritual one, involving long hours at the feet of elders. Traditionally he would have become a sabedor for his community, healing and advising, but his education was disrupted by the intrusion of the outside world. Sharing his knowledge, translated through the medium of drawing, with non-indigenous scientists allows him to preserve this valuable legacy. His drawings also allow him to pass the traditions down to his city-raised son, doubling their chances of continuing into the future.

What strikes one most about Rodríguez’ work in this context is its generosity, a feeling also embodied in the works themselves. The translucent layers of ink create density without overcrowding, the breathing spaces left for birds and mammals and orchids and fruit to be distinct amid the greenery, the detailed labels, and the attention to the whole life cycle of a plant or ecosystem. His way of seeing is generous to the forest and generous to science, to his people and his knowledge, and it seems only right that he takes the oblique benefits of art-world recognition as they come, as he is happy to do. After all, he loses nothing by seeing the sea.

Even if his art is not our “art” but rather iimitya (a Muinane term for ‘word of power’), as he says “all paths lead to the same knowledge, which is the beginning of all paths”. Westerners familiar with Umberto Eco’s book From the Tree to the Labyrinth will note that it took us several centuries and the invention of semiotics to reach the same conclusion. Rodríguez just needed to see the trees.