During the current Coronavirus crisis, we are publishing one article per week from our latest Spring issue. It is also available to read in full via the Elephant app, or a physical copy can be ordered from our online store.

Almost every morning for the last six years, Carrie Mae Weems has started her day by listening to Ode to Life by Don Pullen

, followed by Stevie Wonder’s Love’s in Need of Love Today. “I dance to it, I cry to it, and then I go to work,” she says. The ritual is about paying attention to her creative desires (“It tells me who I am and what I love the most in this world”) and is a reminder of “extraordinary people, resilience, wonder and just going for it every day and being aware that I have a platform”.

Weems, recognized as one of the USA’s most influential contemporary artists, has not only used her platform tirelessly to express her ideas (day in, day out, for more than thirty-five years), she built it from the ground up. Her 1990 work, The Kitchen Table Series, was the first photo series to show the intimate, daily details of a woman’s life from a female perspective, challenging the viewer to reconsider the representation of women in the domestic space. Since that early piece, she has reframed the conversation around race, identity, systems of oppression, power and inequality, as well as the role of photography in tackling these themes.

In her 2019 exhibition, Over Time, at Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg, several bodies of work were brought together to consider “how the past comes to bear on the present”. It’s the first time she has had a solo exhibition in South Africa, and while this is significant given the country’s history of racial segregation, Weems believes that “the way larger society has treated the black community is relevant no matter where you are in the world”. Much of her work is about understanding the interconnectedness of what it means to be a certain kind of diaspora, where ideas have to be constantly negotiated.

“We have never been more divided and fragmented as a society as we are now”

The implications of the past on the present is something that Weems has been exploring since the beginning, and it’s where she finds the “beast of meaning”. She takes an anthropological approach to charting the black experience, which has led her to study the lives of both her ancestors abroad and her contemporaries in the USA. In From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995-6) she showcases appropriated images of slaves, revealing how photography has played a key role in shaping and supporting racism. Meanwhile in All the Boys (2016), she responds to the police killings of black people in the United States, bringing urgent attention to the “brutal authority of the state that is systematically directed against black bodies”.

By looking back to look forward, Weems is able to deconstruct contemporary society in a way that shows how far we have come, but also how far we still have to go. In her series Slow Fade to Black (2009–10) and Blue Notes (2014) she considers how women of colour have not received due recognition for their social and artistic contributions, something which was made painfully clear during a recent trip to Detroit. Weems was visiting for pleasure and wished to stand in front of Aretha Franklin’s childhood home, but was shocked to see no plaque or indication at all that Franklin had lived there. “I was stunned; I was really upset that there was no plaque there,” she tells me. She plans to work with the city to create one.

Still, Weems refuses to get bogged down by the countless instances of inequality that confront black Americans daily. She insists that by engaging with the deeper question of how to advance humanity, each day is an opportunity to do just that. And the most powerful tool at her disposal to further this message is herself.

In The Kitchen Table Series and other bodies of work, such as The Museum Series (2006–ongoing) or Scenes & Take (2016), she draws on the strength of the black feminine gaze by placing her own body in the frame. Initially this decision was almost accidental; she was living in a small town with few black women to act as her subjects. She soon realized that, while it was essential for her to make the work, it was also essential that she was in the work. “I was performing for myself and claiming space regardless of where I was,” she says. “Whether I’m out in the world standing in front of a museum or in my kitchen, it is the same determination to have the body speak loudly and quietly.”

“How do I establish hope for myself and possibility for the future, that is dynamic and authentic?”

In the age of the self (and the selfie) it might be easy to mistake her self-portraiture as part of this solo trajectory. But Weems is part of a generation that grew up during the Civil Rights Movement, where the greater question was about the “we” not the “I”. Born in Portland, Oregon, she grew up in a family that told her she had the right to be part of the conversation. This encouraged a sense of collective responsibility and Weems believes that authentic networking, face to face communication, organization and unionization have all collapsed under the weight of the “I” and the individual. “We have never been more divided and fragmented as a society as we are now,” she says. “There’s a great danger in it. As well as extraordinary promise.”

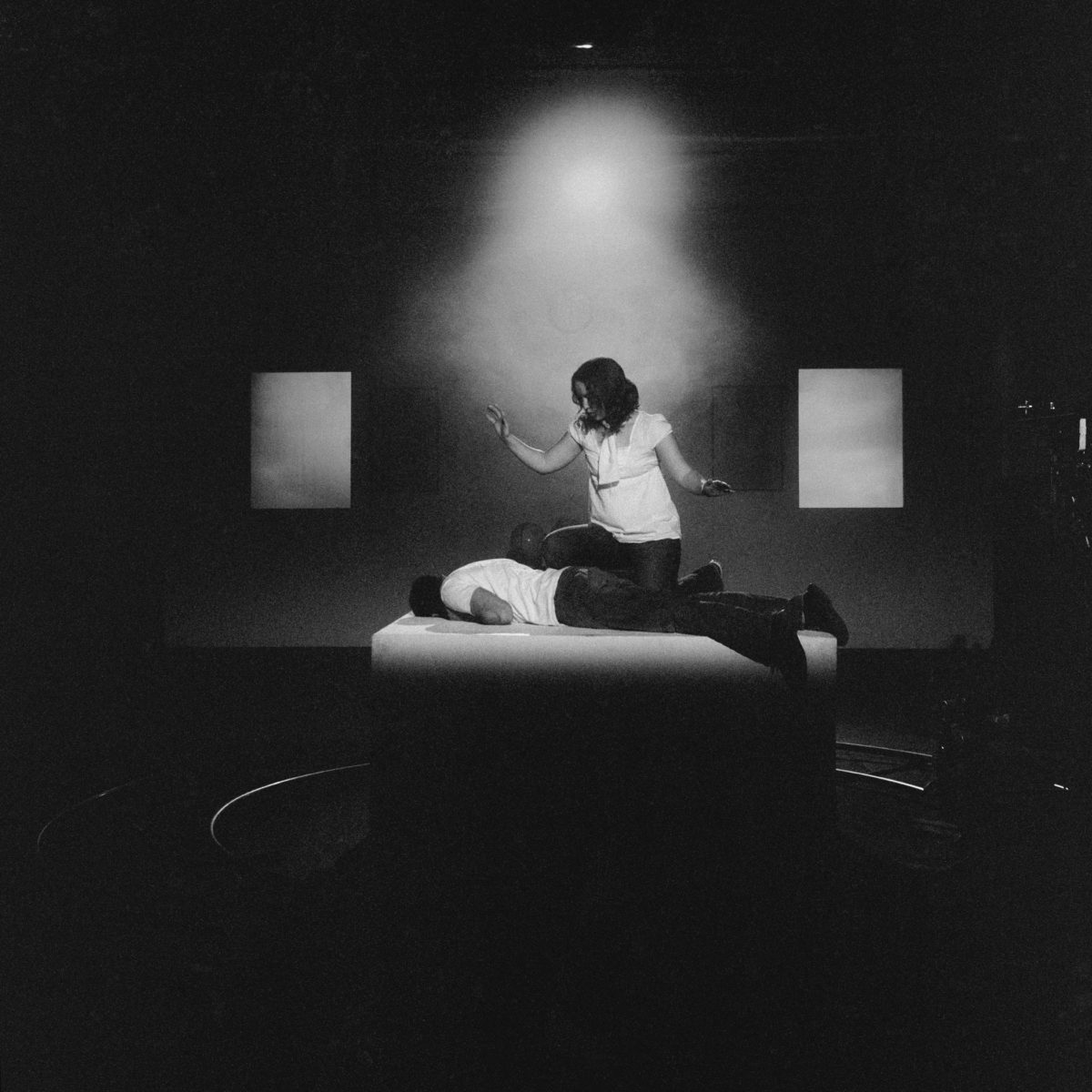

- Left: Carrie Mae Weems, Suspended Belief, 2009. Right: Carrie Mae Weems, The First Major Blow, 2008. Both courtesy the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery and Goodman Gallery

This promise is evident in the big demographic shifts that are happening in popular culture, as gallery spaces, magazines and TV screens that were once dominated by white men, begin to diversify. And Weems’s part in this should not be underestimated. As a performance artist, art-photographer, videographer and activist, she has taken it upon herself to draw attention to how the world is structured, and in doing so, help guide her viewers to other possibilities.

It is a considerable responsibility but one she seizes with relish. “I’m just so excited,” she says. “There are days absolutely that I’m incredibly exhausted, but my drive has to do with asking: ‘How do I establish hope for myself and possibility for the future, that is dynamic and authentic? And how do I bring that to this audience that so desperately needs it?’”

The Elephant Spring issue is available to read in full via the Elephant app, or a physical copy can be ordered directly from our online store.

READ NOW