During the current Coronavirus crisis, we are publishing one article per week from our latest Spring issue. It is also available to read in full via the Elephant app, or a physical copy can be ordered from our online store.

Over one third of Berlin’s inhabitants come from overseas, and it is this multiculturalism that shapes everything from its eating habits to the many languages that can be heard on any given street corner. When Venezuelan-born Sol Calero moved to the city in 2009, she was struck by this diversity, as well as the freedom that it offered, where nightclubs stay open past dawn and studio space for artists is plentiful. It has now been her home for ten years, but memories of her hometown of Caracas remain an important part of Calero’s work and identity. In colourful, immersive wall paintings and installations she hints at her Latin roots, channelling not just her own impressions of the country but its place in the popular imagination. Bright stripes and patterns, fruit and leafy plants abound, and she grapples with these “exotic” stereotypes.

Uneasy dualities run throughout Calero’s work. She explores the historic power imbalance between Europe and Latin America, and interrogates her own blurred identity between the two. As one of Berlin’s many immigrants, she has carved out her space in the city, using her vibrant, densely layered mixed-media work to break down boundaries between art galleries and the wider community. In 2014 she organized an exhibition at a Berlin salsa school, while more recently has focused on the Latin American hair salon as a site of communication and togetherness. In a 2015 exhibition at Studio Voltaire in London, Calero considered the notion of the “tropical”, and playfully tackled the cultural appropriation bound up with the term in a large-scale installation bursting with imagery of ripe fruit and colourful architectural structures.

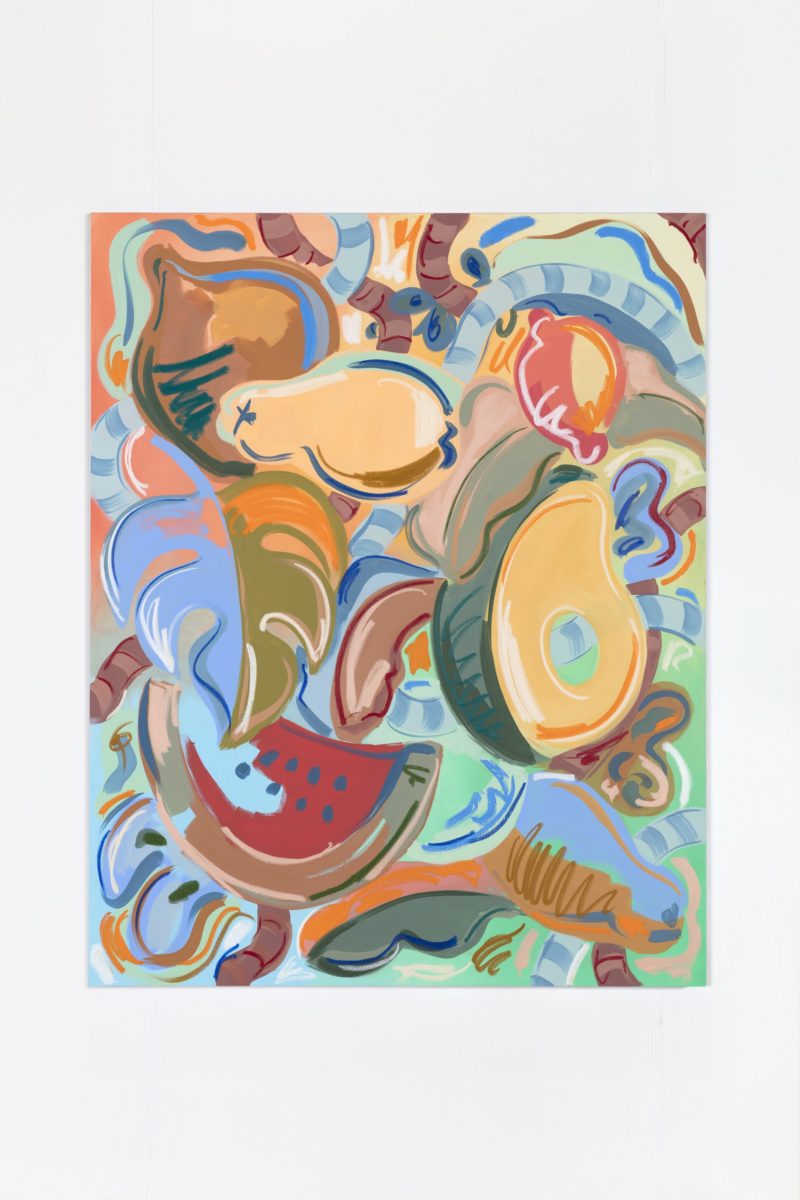

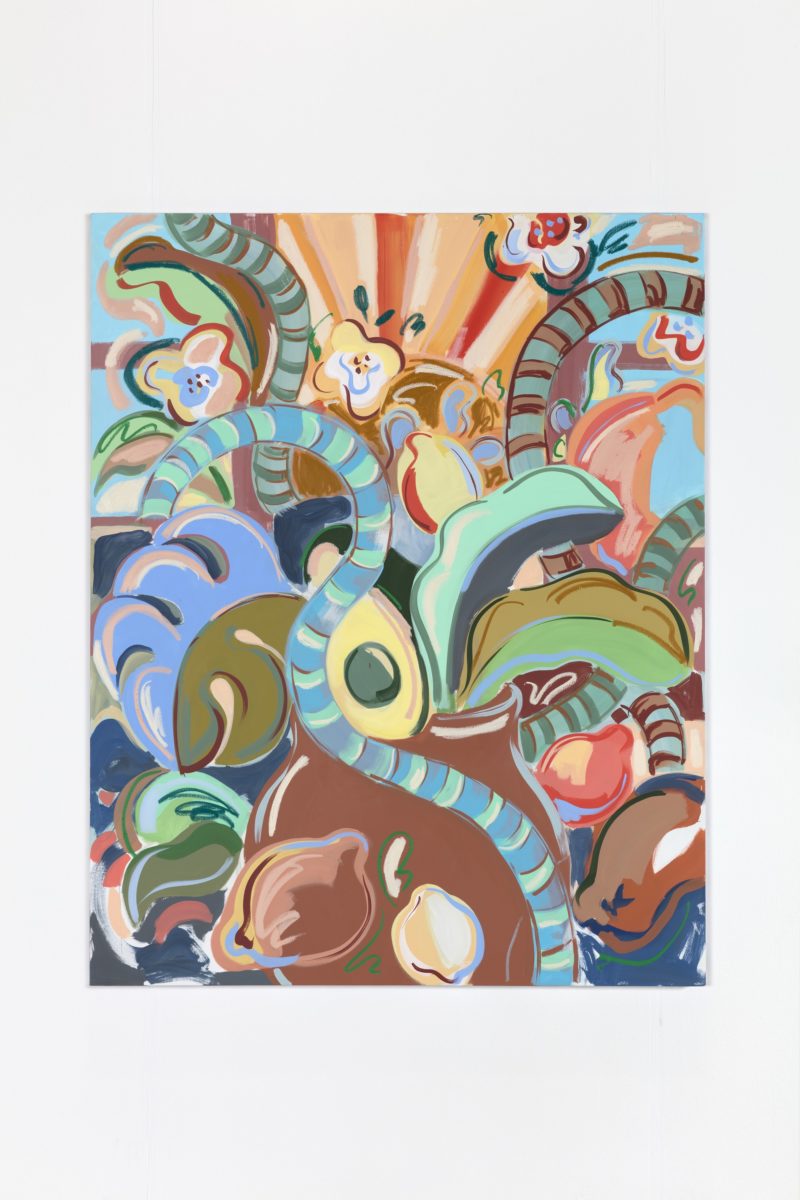

“I try not to paint fruit, but it always comes back,” Calero laughs when I ask about this particular motif, before explaining, “I wanted to dig into the much more painful subjects that had to do with racism and stereotypes and clichés, but I wanted to embrace them and flip them. I wanted to push them until you couldn’t see them as stereotypes anymore, so you can enjoy the real aspects of them—like colour and beautiful nature.”

It is apt that we first meet in the garden of the Brücke Museum, in the outskirts of Berlin, where Calero has recently co-curated a group exhibition with the artist Christopher Kline, who is also her husband and frequent collaborator. A large pavilion by Calero has also been installed onsite. Characteristically colourful, it pushes right up against Grunewald forest, where the elegant German pine trees extend into the distance. We are surrounded by nature.

“Asking someone to integrate is basically asking them to forget where they’re from”

In recent years, Calero’s work has seen her nominated for the Preis der Nationalgalerie, with an accompanying exhibition at Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin in 2017, and she was shortlisted for the Future Generation Art Prize that same year. She often references her Venezuelan heritage but is careful to distinguish her early years in Caracas from her subsequent time spent in Europe. She moved abroad like millions of other Venezuelans in the wake of the country’s political upheaval, and this experience of cross-cultural transition continues to inform her interests. “The way I learned art was as an immigrant. When you move to a new place, you have to integrate. I don’t really like the concept of integration, the idea of becoming Westernized, because asking someone to integrate is basically asking them to forget where they’re from,” she reflects.

“When I first moved to Europe, I wanted to hide my identity; I didn’t want people to know I was Latin because people were very racist against Latinas in Spain. So you move—and I was only seventeen—and you’re in fear. But this all made me feel that I wanted to go for it and do something that had nothing to do with who I was trying to be.” Calero studied in Madrid and the Netherlands, where she began to establish her distinctive, maximalist style, and experimented with scaling up. “Once I started doing these big colourful paintings, I began thinking: ‘This is natural, I grew up with this; with this colour, with this light.’ And even though I started out from this critical position, I started to feel: ‘Oh, this is beautiful and fun’, and I began feeling much freer because now my palette was so big! In the end it’s my own decision, and I can use 100,000 colours.”

Calero’s points of connection to her own culture come through in these aesthetics, drawn from her early years and reimagined at a distance. “These are my memories from Venezuela, but what happens when those places are not what they used to be?” she asks. “Then you’re referencing places that don’t exist anymore and you’re using the power of your memory to recreate them.” Calero’s latest exhibition at Tate Liverpool, her biggest to date, tackles this duality. Titled El Autobús, it explores the richly decorated buses popular in Latin America, which cover essential commuter routes while tourists make use of them as part of the mythologization of the local area. Like much of her work, it presents a tension between a Western-centric perspective on the world and its lived reality.

Calero herself must contend with her own divided identity. “I’m now more in the position of asking: ‘How do you feel when you don’t belong to any place?’ You are in this sort of island where you have to look wherever you are in a completely different culture, and the adaptation process is very difficult. It could be that you never will belong to a place.” Her work is an attempt to approach these difficult themes with a lighter, more positive touch, offering a utopian view on this sense of placelessness and instability.

“I think humour is quite important for me,” she asserts, “although maybe this is the first time I am saying it like this. It’s not like that is the main point of my research, but it was a part of how I grew up in Venezuela and in Latin America and the Caribbean. People’s reality is so difficult that you have to find a way to distract yourself, and things seem less important than they actually are—perhaps it’s just so overwhelming. The way you live there is experienced in terms of the everyday, you can’t think of the future.”

“These are my memories from Venezuela, but what happens when those places are not what they used to be?”

Community is important to Calero and her work. She has co-run the project space Kinderhook & Caracas with her husband Christopher Kline out of the couple’s front room for eight years, showing the work of mainly Berlin-based artists. “It can be hard work—you have artists in your house all the time—but you work closely with them.” Budgets are limited, and the pair produce everything themselves for the space. “It’s important to not only be thinking about your own practice, but also how you can be learning from other artists too,” she explains when I drop by the space. It’s all high ceilings and wooden floors; the walls are left white for artists to work with. Calero’s private living space, on the other hand, is a riot of hand-painted colour and homemade furniture, firmly in keeping with her characteristic visual style.

It is an aesthetic informed by the lived-in, highly personal touches of the spaces occupied by diasporic communities in cities around the world. One of Calero’s first projects was in London, where she visited Elephant and Castle to research the area’s Latino and African hair salons. “There is a social aspect to these places, like a hair salon and a restaurant, especially for immigrant communities, where they exchange goods and information. Decoration has a lot to do with that, it has a lot of responsibility in that sense. When a Mexican person moves to a new country and they want to open a Mexican restaurant, they have all these different creative elements that will identify it, not only the food.”

Her work continues to reference this early research. “I started looking at these businesses and how they represent themselves as Latin Americans, or Turkish or Chinese. What do you use for these representations?” Calero herself created a temporary restaurant as part of the project (“It was really bad food,” she jokes) and offered drinks and a convivial atmosphere to visitors.

“There is a social aspect to these places, like a hair salon and a restaurant, especially for immigrant communities”

Calero still welcomes collaborators, often working with other artists and local communities. In 2017 she built a pavilion as part of the Folkestone Triennial with a team of people from the area. The pavilion—originally intended as a temporary structure—has stayed put ever since, after the community stepped in to request that it remain. “I love that connection,” she says, smiling.

“I think that this impulse to connect comes from writing music, partying every weekend for years when I was younger and also going to concerts; music has this special connection with people. Art is different, so whenever I do an exhibition, I think about how I can connect in the way that music connects.” Her bright, tactile, highly social work bursts free from the constraints of the art gallery. Instead, Calero embraces the messy, communal reality of everyday life. “I’m thinking, how can you make people feel through their bodies? How can you see something and let it take you somewhere else?”

The Elephant Spring issue is available to read in full via the Elephant app, or a physical copy can be ordered directly from our online store.

READ NOW